After such a wet spring why aren’t all of our wetlands full?

People who travel a lot around the near-border region of SA and Victoria and take an interest in wetlands, are currently rejoicing in the fact that many wetlands that haven’t filled in years are bursting with life – and this is happening right now, as you read this blog.

After two failed spring seasons in 2014 and 2015, above average rainfall in September and October this year has made a huge difference to the fortunes of so many of our wetlands. Bool Lagoon filled with record flows very quickly and will now be a hot-spot for countless species of wildlife over the months ahead. All of NGT’s wetland restoration sites on private and public land are looking absolutely fantastic, meaning that we are getting to see exactly what a difference restoration can make.

For just one example, here is Green Swamp.

But like me, has anyone else noticed that not all of our wetlands are full? In fact, some really important wetlands closer to the border zone remain completely dry.

There is a pattern to all of this I have noticed that is worth sharing, because where the water remains in the landscape and crucially (as we head into the summer months), how long it will last in many wetlands (including some of those that have now filled with surface flows) is often linked to one key ingredient – and that is, depth to groundwater.

In the near border zone, where the stringybark forests over deep sands occur, this trend is most apparent – because it is an area where many of the wetland features are landlocked (they receive limited or no surface run-off have no obvious wider catchment feeding them) – meaning they are 100% dependent on the depth to the groundwater table for their water supply. In a nutshell, if shallow groundwater doesn’t intercept the surface any more, then many of these wetlands will remain dry – and if they do inundate, it will only be for very brief periods after heavy rainfall, until the puddles seep away.

One large area that fits this description includes the nationally (DIWA listed) Boilaar Swamp chain of wetlands (in Roseneath State Forest) and Lake Mundi – an area that (to get your bearings) is roughly situated between Penola and Casterton, just on the Victorian side of the border.

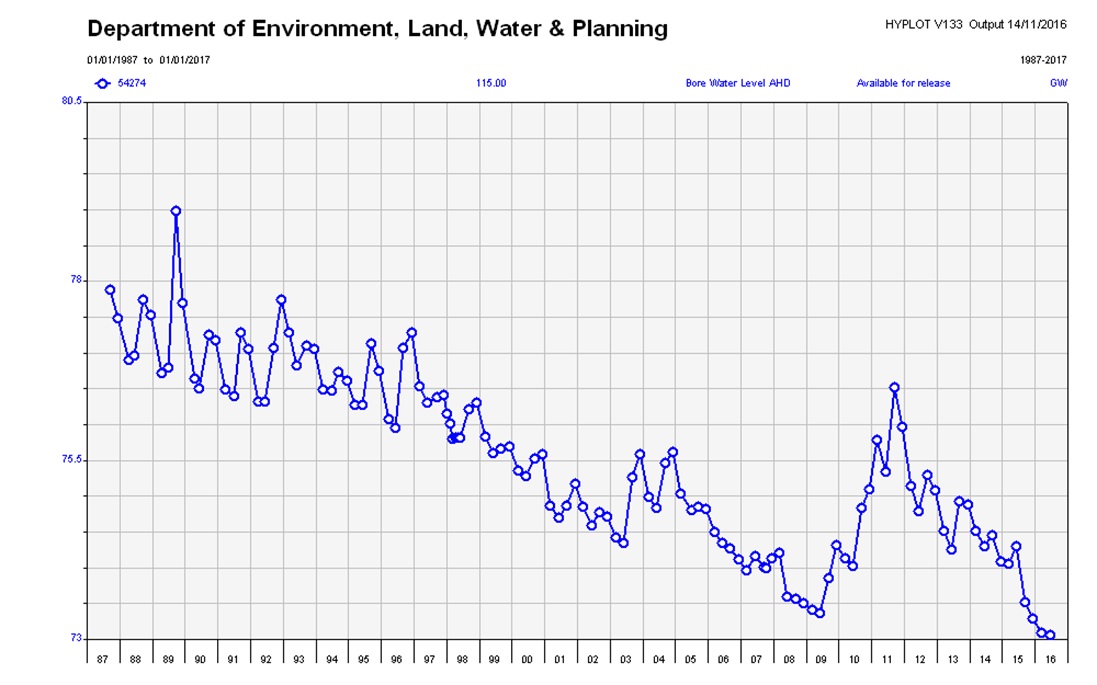

The nearest DELWP groundwater bore data to this site illustrates a trend that perfectly explains what we are seeing play out above the surface.

Aside from the spike associated with the short “big wet” we experienced 5 years ago, this area – like so many others across the region (both sides of the border) – is undergoing a long-term phase of groundwater level decline. One of the primary drivers of this change is climate, but we also can’t underestimate the impact that recharge interception and groundwater use from other land uses in the surrounding landscape is having in exacerbating this trend. In other parts of the region, deeps drains are also capable of both reducing recharge and depleting/lowering groundwater, which makes it harder for the landscape to ‘wet up’ and then to retain that water through the summer, when and if it does inundate again.

Despite record flows in the Mosquito Creek Catchment (nearby to the north) this spring, it is clear that one wet year in our “deep sands” country isn’t enough to achieve the level of groundwater recovery required to bring these swamps back to their best. So it will be very interesting to see how this wetter year influences the trend (shown above) in the next bore reading – but more importantly, let’s hope we experience another similar wet year (capable of significant recharge) again next year – and maybe, just maybe, we’ll see a few more of our important groundwater dependent swamps in this highly biodiverse area fill once again…