Important news for Karst Springs of the ‘Limestone Coast’!

With little fanfare (although that may still be to come!), in the past couple of days we’ve noticed an update to the EPBC Act list of threatened ecological communities in Australia, on the Australian Government website.

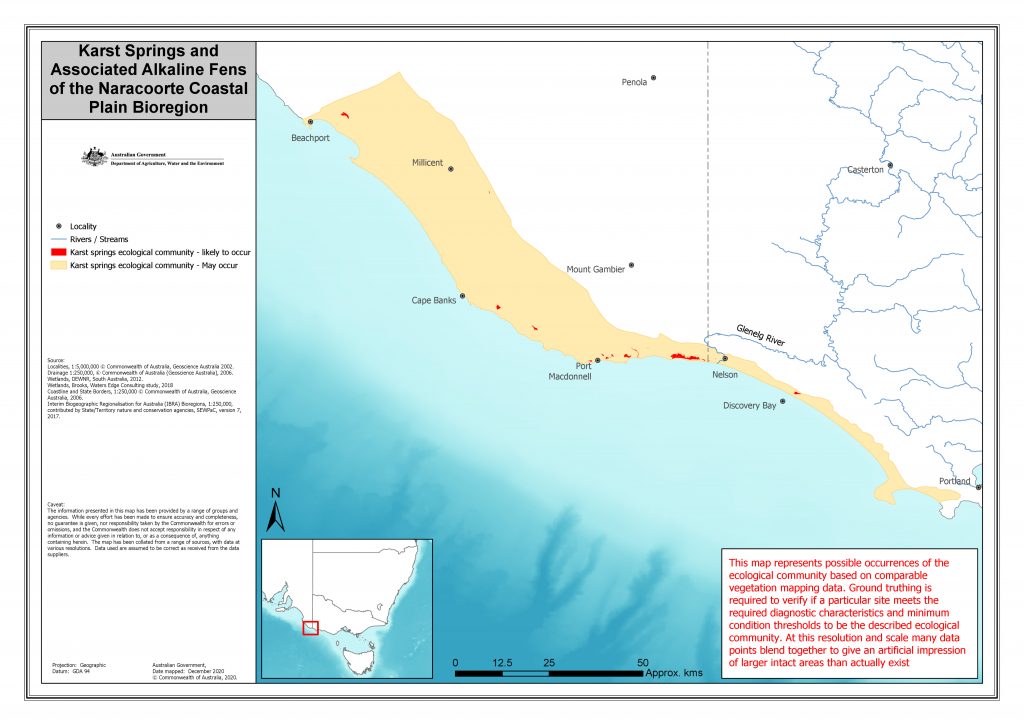

On the 15th of December 2020, the Karst springs and associated alkaline fens of the Naracoorte Coastal Plain Bioregion ecological community was listed as endangered at the national level. For a naturally rare ecological community with a very restricted distribution, as shown below, this is big news!

I deliberately used the term limestone coast in the title because although this expression is now sometimes used to describe the entire South East region of SA, the limestone geology that typifies this region (and is a necessary ingredient in the formation of karst springs and alkaline fens) doesn’t stop at the border, and extends into western Victoria. Parts or all of some places we have spoken a lot about over the years, like Piccaninnie Ponds, Pick Swamp, and Long Swamp all provide well-known remnant examples of karst springs and alkaline peat fens.

These sites have also been the subject of successful hydrological restoration projects – and this is where the EPBC listing of this community is especially important, because it creates the possibility of helping us to do good for both the karst springs landscape, and our water resources, which have both been negatively impacted by intensive drainage of the unconfined tertiary limestone aquifer in this narrow coastal zone.

Many people view our national environmental laws as a necessary (and yes, sometimes unpopular) means of preventing new harm to threatened environmental features or species, which is a legitimate function of the legislation, but importantly the story doesn’t end there. Despite common fears that sometimes exist in rural communities – the EPBC Act is not retrospective legislation and cannot force anyone to change land management practices that have already been in place for many years or decades. That means the threats that have driven an ecological community to becoming threatened are not somehow magically solved by the listing alone – it is just the beginning of the conversation about what to do next, and by necessity this means working cooperatively with people who are interested in identifying solutions.

Which leads us to a less frequently discussed, but absolutely vital role the legislation can and does play in providing incentives for recovery: the listing helps to focus everyone’s attention on the key issues and can also attract additional investment in novel solutions.

And this is where the karst springs story gets really interesting, because despite the number of threats facing this very restricted community (and there are many), we also know that it can exhibit incredibly fast biodiversity recovery, even from a quite degraded state – as the Pick Swamp example attests. Best of all, restoring these near coastal spring-fed wetland features also helps to buffer local groundwater resources, by retaining more groundwater in the surrounding unconfined limestone aquifer. This is very good news if you are a neighbour with a bore that relies on groundwater – a real win-win!

The zone where these solutions are especially viable, because many of the drains still reliably run with water, even if now only for a few months every year, are in the former coastal wetlands fed by springs that are dotted around the coast between the border and Carpenter Rocks (see map below). In a number of these former wetlands, there is not much habitat left, but with a bit of foresight, cooperation and imagination – just like Pick Swamp – some of them could one day be brought back.

To learn more about the listing, please visit the Australian Government’s listing page, read the conservation advice below, or download the pdf here.

149-conservation-advice