Nurturing nature – the many benefits of getting outdoors

During Mental Health week this year (12-16th October), I took the opportunity to stop and think about what has been a challenging time for us all. I have been reflecting on the incredible resilience people and communities have shown. People deal with adversity in different ways, but for me, spending time outdoors has eased the challenges of 2020, and I know I am not alone.

I suspect that for all of us at NGT, part of the reason why we were drawn to ecology is the opportunity to be outdoors in nature. An opportunity to restore, conserve and protect our natural resources. Conserving biodiversity is obviously critical and an important objective in its own right, but perhaps we don’t always consider the many other ways nature is good for our health.

Eco Therapy or Nature Therapy is increasingly becoming recognised in mainstream health care, following research that clearly shows the benefits of being in nature. In Japan, people have been immersing themselves in the woods since the 1980s as a way of combatting disease and illness. Studies show that shinrni-yoku – which literally translates to ‘forest bathing’ – can reduce blood pressure, lower cortisol levels, improve sleep and improve concentration and memory. What’s more, trees and plants are known to release a chemical called phytoncides which have been found to boost immunity.

Forest bathing, which refers to mindful time spent under the canopy of trees for health and wellbeing purposes, has long been incorporated into the health care system of Japan. Interestingly, it’s taken some 40 years for healthcare systems in western countries to catch on and adopt similar philosophies. Time in nature is now one of many non-clinical activities that doctors and other professionals are prescribing to improve people’s wellbeing. Green prescriptions have been offered by professionals in the US for over 10 years and are currently looking at being trialed here in Australia.

While western culture has only recently recognised the role nature plays in improving our wellbeing, connection with the land has been an integral part of Indigenous culture for thousands of years. I recently had the opportunity to attend a virtual conference hosted by the Australian Association for Bush Adventure Therapy (AABAT) where Pakana/Bunurong elder, Aunty Verna Nichols, and local Boandik man Ken Jones shared a beautiful Welcome to Country and inspiring presentations. The symposium highlighted the need to respect and learn from First Nations knowledge and their innate connection to land. The ancient Aboriginal practice of Dadirri (a Ngan’gikurunggurr and Ngen’giwumirri word meaning deep listening or something akin to meditation) reminds us to use our senses to slow down and be still. Luke Mabb, a Wakka Wakka man, beautifully summarises the importance of connection to land…

“if we’re healing our country, we’re healing ourselves.”

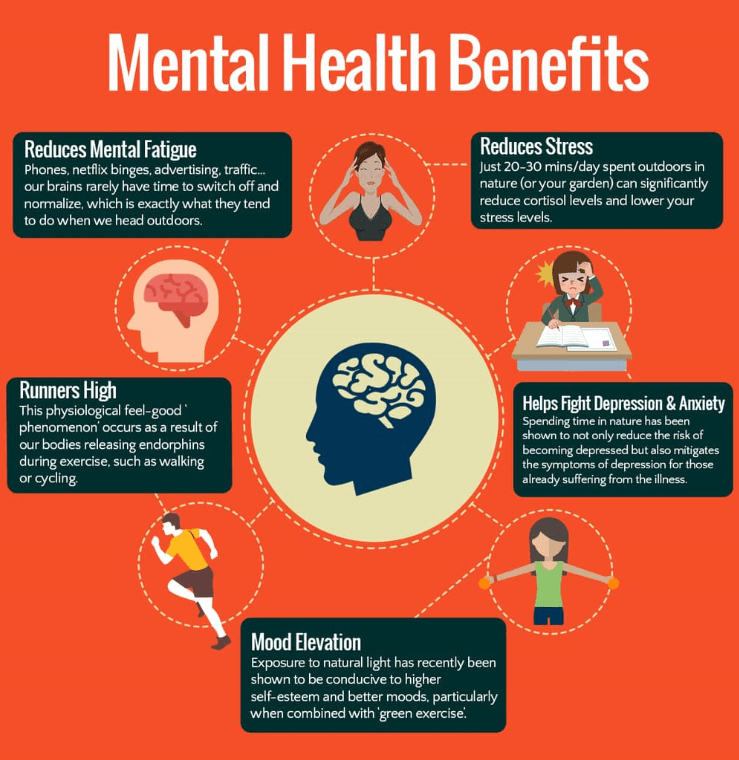

So what is it exactly about nature that’s beneficial? In its simplicity, the endless boundaries of nature and the absence of rules or limitations present an opportunity for anyone to learn, explore, observe, directly experience and grow. Stepping outside into nature provides a rare chance to break down social barriers, stigmas, stereotypes or prejudices (since we all have an equal capacity to connect with nature). It has been proven to increase focus and cognitive processing ability and push us beyond our comfort zone, to achieve peak learning. Recognising that nature is dynamic and forever changing can promote adaptability. I feel this point is particularly pertinent in relation to 2020, since we have all needed to become a little more flexible and accepting of change and the unknown.

The opportunity to engage in conservation work and assist in healing the landscape creates a sense of purpose and belonging. After all, we are all just a small part of a much a larger landscape. It creates connection with not only nature but also other people, which for some, provides an important pathway for combating social isolation or loneliness. At the same time, for people who find themselves more reliant on extrinsic factors in life, may realise they don’t need the constant social contact or material possessions to feel content.

At NGT, the undeniable mental health benefits of nature and the conservation work we do is something we have sometimes reflected on in the past. Last year, Mark and Lachie attended a forum at Winton Wetlands which focused on “Connecting People with Nature” and the role of nature in both ecosystem health and human health. Mark gave a great talk on the unintended outcomes he had observed in NGT’s wetland restoration trials that have had significant volunteer involvement.

Not only was assisting with sandbagging and working with water different to the normal types of volunteering that people are usually involved in, but it gives a sense of personal and collective involvement in solving an environmental problem (and sometimes seeing immediate results) which is very rewarding. It also provides an educational opportunity, a chance to build a connection with the site, and with others who share a similar interest.

No NGT project has summed this up more than the trial structures completed at Long Swamp. The sense of camaraderie, common purpose and satisfaction felt by the dozens of volunteers who helped us with hundreds of hours of volunteer labour to complete the trials at Nobles Rocks was tremendous. The final major structure consisted of over 7,000 sand bags, and would never have been completed if not for the dedicated help of so many volunteers.

Through spending more time at home this year, I have learnt to appreciate the smaller offerings of nature. Watching my inquisitive young son take a keen interest in a leaf blowing in the wind, a butterfly hovering over a flower or a bird calling in a tree has been a welcome reminder of how we all entered this world with an endless amount of curiosity. This time has highlighted we don’t necessarily need to venture into a National Park to get a dose of nature. We can simply take a stroll in our local park or appreciate the pockets of greenery that exist in our own backyards.

Research has shown that mental health concerns among Australians have become at least twice as prevalent in the current pandemic compared to non-pandemic circumstances. More locally, a recent community survey led by youth councillors of Warrnambool found that two in three people have been experiencing higher than normal stress levels in 2020. For 97% of respondents, being outdoors in nature was the most useful activity for maintaining mental health. Findings such as these from 2020 help strengthen the argument for the need for urban planners to ensure people have access to green spaces in their community, and for all of us to continue to maintain our connection with nature. I hope you are able to enjoy some time outdoors today!