The fishes of the Surry Estuary

Last month Lauren B and I spent a few days sampling the Surry River estuary in Narrawong, south-west Victoria. This small pilot study aimed to look at possible sampling methods and locations for a longer-term program to build more understanding and community awareness around the species of fish that occur in the estuary, and how they change over time and under different hydrological conditions. We trialed a few types of nets which targeted smaller bodied and some lesser-known fish that don’t usually appear in recreational catches.

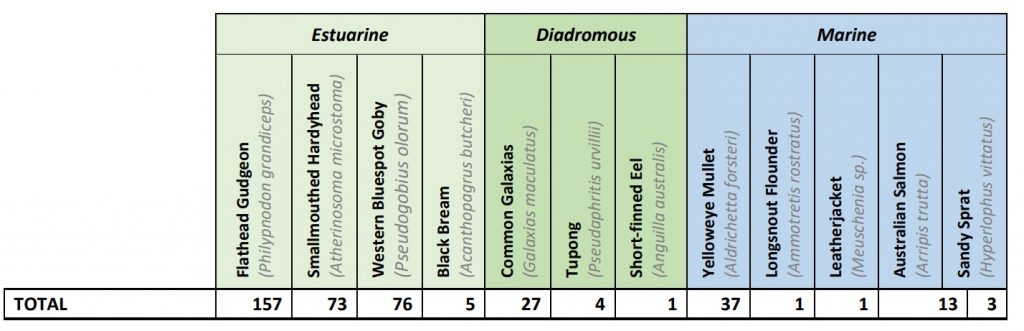

The Surry estuary has remained open since June this year, receiving significant flows during spring and early summer rain events. The dynamics of this intermittently open estuary allows for a diverse array of fishes and during the sampling we recorded 12 species of fish within three general groups; estuarine fishes that are dependent on the estuary environment during important life stages, marine fishes that mostly spawn in the ocean but opportunistically enter the estuary, and diadromous fishes that regularly migrate between sea and freshwater to breed. You can see the species and total catches in the table below.

The species caught in highest numbers – the Flathead Gudgeon – is a hardy little fish that may be comparatively smaller in size to other predatory fish but is a stealthy ambush predator that camouflages within the substrate of the estuary. Other abundant small-bodied estuarine fish included the Smallmouthed Hardyhead and Western Bluespot Goby which have a broad tolerance to salinity levels and thrive within the estuary during its opening phase. A few decent-sized Black Bream (235-360mm) were also caught in the fyke nets. Bream spawn in the upper reaches of rivers and streams usually during late spring, so while we didn’t sample any juveniles in this effort we may expect to observe more from early next year as they start to travel downstream.

An amazing fish to see was the Tupong which has a very interesting diadromous lifecycle: female Tupong travel downstream in response to high flows to spawn in the bottom estuary or sea (the mature males stay within the river system), and then the juveniles migrate upstream into freshwater during spring and summer to feed and shelter. Tupong are one of very few fish globally, that show disparate migratory patterns between females (diadromous) and males (non-diadromous). The winter flows, as well as the timing of opening and closing of the estuary are therefore important for the species spawning success and lifecycle completion.

We also caught one sneaky (and rather large) Short-finned Eel. I was quite relieved that Lauren B took on the challenge of safely returning the eel to water. Short-finned eels also migrate to the ocean (all the way to the Coral Sea in New Guinea!) to spawn and can live up to an impressive 24 years! This incredible species, also called Kooyang in Dhauwurd Wurrung, is very important to the Gunditjmara who for many thousands of years have taken advantage of this downstream migration, successfully capturing the eels in elaborate and extensive aquaculture systems encompassing floodplains and rivers.

Marine species such as the Yelloweye Mullet and Australian Salmon are great eating fish and popular ocean catches in Narrawong. Our sampling showed the lower estuary of the Surry provides an important nursery area for the juveniles of these schooling fish. One interesting catch was a very small (50mm) Longsnout Flounder which characteristically has both eyes on one side of the body – a perfect adaptation for sitting on the substrate of the estuary (usually) undetected.

This survey provided an excellent snapshot of the diverse range of fish species reliant on the Surry River estuary. Future monitoring, when the Surry River estuary closes to the ocean, will provide further insight into the dynamics of this system and how mouth opening and closures influence the fish communities. Involving community members in future surveys, will provide a unique opportunity for residents (and tourists) to learn more about the broader aquatic values of the Surry River.