A rare chance to “look under the bonnet” – answering your most common questions about the inner workings of NGT

Over the past 8 and half years, I have been regularly asked all sorts of questions about Nature Glenelg Trust (NGT) – usually when out and about at community events or when giving presentations to community groups – I guess mainly because NGT seems a little bit different in one way or another to what people might expect from an organisation like us.

Combined with an excellent discussion we had at a recent catch up with our colleagues at the Glenelg Hopkins CMA, I’ve come to realise that a few things we take for granted inside NGT are not necessarily well understood by the many people we regularly work with across south-eastern Australia.

So this is the chance to share some of those common questions and answers with all of our newsletter subscribers and supporters, to give you some deeper insights into how NGT ticks!

(Reader warning – we get asked lots of questions, so this is a long article…)

Q: How did NGT start and was a philanthropic benefactor involved?

No, unlike many non-government, charitable, not-for-profit organisations, NGT did not have any seed funding provided by a philanthropist – in fact, philanthropy didn’t begin for us until a little later, because extended processing delays with our paperwork meant we didn’t obtain DGR (tax-deduction) status from the ATO until May 2014.

The original NGT Committee of Management:

From Left to Right: Nick Whiterod (2011 – 2021), Michael Hammer (2011 – 2021), Becky McCann (2011 – 2013), Lachlan Farrington (2011 – 2023), Melissa Herpich (2011 – 2019, 2022 – 2023), Cath Dickson (2011 – 2022), Mark Bachmann (2011 – present).

NGT itself simply started as an idea, and you might also be surprised to learn that this idea actually began as something of a running joke. Let me explain…

I suspect that I am not the first person who has worked in a state government environment department, to be in situations where you or your colleagues might occasionally say “we should just start our own NGO!” – in exasperation with bureaucracy sometimes inadvertently getting in the way of common sense conservation outcomes. So it was in early 2011, after hearing it said many times over the years, that I found myself repeating this idea more frequently, initially just in private conversations with one of my close colleagues, Melissa Herpich, whose office was situated next to mine at the time in Mount Gambier. A subsequent chain of events later (a longer story for another day…), and what began as a joke started to take on a life of its own – at least initially in my thoughts, as I began pondering the possibilities, the different potential models and whether it could work. The upshot of that process is that it did seem increasingly obvious to me that this concept was worth attempting, for a whole range of reasons (some of these are addressed in later questions).

I subsequently made confidential approaches to six trusted colleagues (Melissa Herpich, Cath Dickson, Lachlan Farrington, Michael Hammer, Nick Whiterod and Becky McCann) and I asked them to join me in forming a Committee. After our many early discussions and even more late nights working on behind the scenes tasks; NGT was legally established in October 2011, launched publicly in January 2012, and here we are all these years later. It has been quite a journey!

We’ve had wonderful support from some incredible people ever since, but the thing I am definitely most proud of in this story, is that we managed to start NGT as a group of regular people: from the ground-up, very much against the odds, from scratch. We began with literally $0 in the bank, but what we lacked in finances we definitely made up for with passion and commitment!

Q: Why does NGT have paid staff – instead of just volunteers like other community groups?

Similar to many community groups, NGT has largely been built on the “sweat equity” of our Committee, staff and volunteers, who have been determined to see the NGT experiment succeed. The fact that some people (our paid staff, myself included) can make working at NGT their main focus of employment has actually been critical to our success – because it allows for a form of dedication that is difficult to achieve if you are still in an age bracket where most of the week would otherwise have to be spent working somewhere else for income. We also live in an era (thankfully) where environmental science is a recognised and necessary profession in its own right – notably this is a career option that never existed for members of the amateur field naturalist groups that typically commenced from the 1950s. We really do owe so much to these groups who came before us, and we now regularly work with, because everything they achieved was done within these constraints.

Hence, for myself and our other paid staff, the job at NGT is an unusual blend of profession, vocation and hobby – which I realise can be difficult for outsiders to understand when, for many people in society, work is deliberately kept separate from their private interests. So yes, NGT staff regularly volunteer time well beyond their official recorded hours and also donate to NGT’s fundraisers. We also have many dozens of wonderful volunteers who are not paid at all, and are equally committed to what we do.

In fact, there are many times that we would have been completely lost without the incredible commitment of both our paid staff and volunteers working together, going ‘over and above’, in all sorts of ways to get things done. Across the board, our people are our biggest asset and a great bunch to work with.

Q. Are any of your office jobs done by volunteers?

Our longest serving volunteer also happens to be my father-in-law, Richard Crew, a retired accountant and business manager with a lifetime of expertise gained from within the private sector. Richard remotely manages NGT’s finances and payroll from his home office in Adelaide and has been with us since mid-2012, when I (very wisely in hindsight!) accepted his generous offer for assistance. We only had (I think) three staff at the time, but more were on the way and I was already being pushed beyond my capabilities in this domain. Despite the fact that Richard is not paid for his work, his role is absolutely fundamental to our whole operation – we simply couldn’t function without it. We would also otherwise have to pay someone to perform this job, which also greatly helps our bottom line and hence ability to focus on environmental outcomes.

At one stage we also had a fantastic office based volunteer co-ordinator (Kimberley Height), but since she moved on to paid work in Melbourne we have not yet found another volunteer with the right skills to perform this really important function.

If you have a particular set of skills that you think we might need, and are willing to volunteer with us, please get in touch – we’d love to hear from you.

Q. What other volunteering opportunities exist with NGT?

Richard falls into the first of the two most common categories of volunteers at NGT: namely, people that are looking to contribute to a worthy and meaningful cause in their retirement. Whether it be in our nursery or across our Reserves, there are many people who are providing us with incredible support, in a range of different ways. Here are just a couple of examples:

- Dave Lawson

- Gordon Page, Sue Black and John Hargreaves (plus Kimberley Height – who was not a retiree, but is referred to above)

The other most common type of volunteer we have supported over the years are younger people: students and recent graduates looking to learn about environmental science or gain critical field experience to complement their academic training. Here are the reflections of just a few of our many interns:

While these are the most common types, we have lots of other volunteers too, of all ages and walks of life… If you are interested, click here, to learn more about volunteering with NGT.

Q: How on earth does NGT pay its staff?

This is one of the most common questions, especially from members of the aforementioned community groups who are wholly volunteer based and can’t imagine carrying the financial burden of paying lots of employees. The short answer is that it isn’t easy, and is a constant juggling act. Needless to say, in overseeing the smooth running of NGT, this is something that is always at the back of my mind.

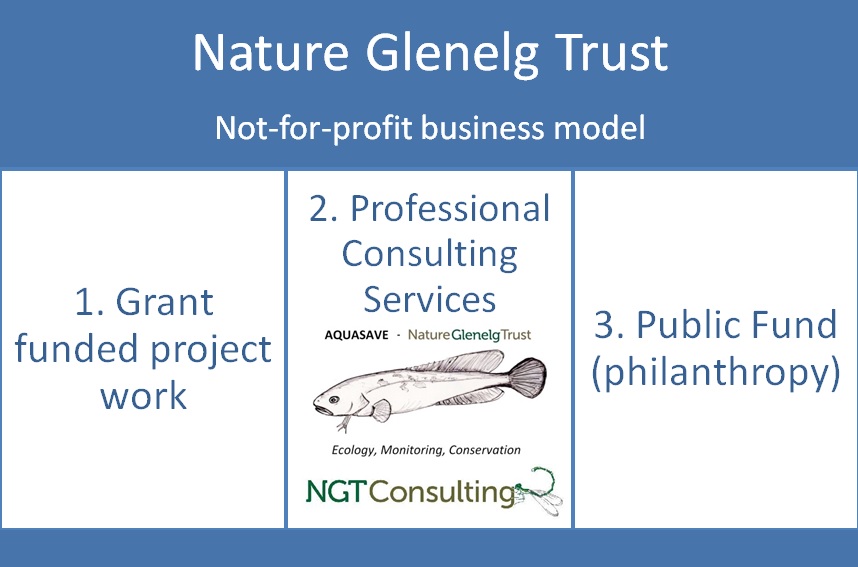

Because we don’t have any recurrent (ongoing) funding sources, our staff are paid by delivering environmental projects, which means those projects need sufficient budgets to pay for staff time, operating expenses and any associated works for on-ground projects. Our projects are generally funded via one of three ways: through grants, professional fee-for-service contracts or by philanthropic donations – as shown in the diagram.

Typically, the main way we pay our staff is through the first two methods of securing funding. This is how we managed to start NGT’s operations from scratch (I might say after a very lean three months of running on empty first!) and were eventually able to stand on our own two feet, without the help of financial donors. Because the timing and duration of projects is highly variable, creating even workflow and guaranteed employment for our staff can be tricky at times. Despite this ongoing challenge, we’ve managed to keep a very stable team of dedicated and wonderful people together now as paid staff for several years – that longevity and experience is valuable to us in so many ways, especially in building trusting relationships in the communities we work with.

As a result of this business model, the vast majority of philanthropic donations have been used to assist with strategic land purchases for restoration projects (see a later question for more on this). To date, we have not specifically fund-raised to cover general operating expenses.

Q. What makes NGT different to regular consultants?

Despite offering some similar services, we are different to a regular consultant in a few important ways:

- Not-for-profit: Consistent with our charter, NGT does not prioritise what others call profit (or what we, as a not-for-profit, call a ‘contribution’ from our consulting jobs) ahead of project outcomes. Outcomes always come first – sometimes to our financial detriment! That said, wherever we can, we try our very best to land ‘in front’ financially on these jobs, because they provide incredibly important revenue to help keep our whole not-for-profit organisation running. In contrast, the vast majority of regular consultants are straight ‘for profit’ enterprises.

- We won’t accept any job: We are careful about what projects we agree to work on, which means that we reserve the right to say no to any job. This means we don’t accept the often lucrative consulting jobs associated with development. Put simply, our philosophy is to only work on projects that lead to improved environmental outcomes, which are consistent with our charter.

- Commitment beyond the job: Irrespective of how a project is funded, we’ll voluntarily invest our time before a project starts and beyond the project completion date, if we feel that we can contribute to better environmental outcomes, or help address issues that are left unresolved. In this way, we think of our relationship with clients as a more of a long-term partnership.

Q. Are your consulting services run separately to the rest of the organisation?

The short answer is no.

This has also come up a lot over the years, especially from people we work with in government organisations who are curious about why we have additional trading names: Aquasave-NGT and NGT Consulting. The explanation is two-fold and pretty simple.

Firstly, we wanted to recognise the commitment and generosity of Dr Michael Hammer, founder of Aquasave Consultants and NGT Committee Member, who donated his private business to NGT as a going concern back in mid-2012. Although Michael has been working full-time in other employment in the Northern Territory since then, retaining the Aquasave name (for aquatic ecology consulting) has allowed us to maintain that sense of connection with Michael’s former clients and the history of Aquasave that began 10 years before NGT existed. Our Aquasave “branded” projects have been overseen by Dr Nick Whiterod ever since.

Additionally, when we started NGT we were keen to ensure, in marketing our services as consultants, that we presented ourselves in a way that would establish our credibility as professionally trained and experienced scientists (we didn’t want to risk being dismissed as “just another charity”). So we also registered NGT Consulting as a trading name, to also allow us to clearly market our credentials for general ecological consulting services.

All trading names of Nature Glenelg Trust are held under the same not-for-profit ABN (23 917 949 584) – so there are no separate entities. In fact, aside from being a “badge” or “veneer” that we place on relevant projects, it might sound boring, but there is literally nothing more to it.

Hence, when you see the NGT annual report each year, this includes the consolidated figures for all of our projects, irrespective of how they are funded by our partners/clients, or branded by us.

(Footnote: in 2023, we retired the formal use of our consulting trading names, operating all of our projects and services under the Nature Glenelg Trust name.)

Q. Are grants and fee-for-service contracts treated differently?

Behind the scenes we only maintain a single list of projects, irrespective of how they are funded, and NGT staff work seamlessly across all grants and fee-for-service contracts, often some of each during a single fortnight. So everything we do is managed within the one set of financial accounts, and delivered under our not-for-profit charter. So in terms of how our staff are asked to work on these projects and our commitment to outcomes, there is no practical difference.

However from an administrative point of view, there is one key difference in how these projects are managed on our books which is linked to the way the project agreements are set up:

Firstly, grants typically have an administration fee charged on them of around 10% to help cover our running costs (this percentage is usually fixed in the grant guidelines), and grants usually pay in advance. So the administration fee is applied to the grant revenue when it is received and the balance of the grant is then spent down to $0, as we deliver the agreed project milestones under the grant agreement.

Conversely, fee-for-service contracts (i.e. consulting jobs) typically pay in arrears – which means we do the work first and get paid for it progressively in stages or upon completion. Unlike grants, fee-for-service contracts do not have a set administration fee. Rather we simply complete the work, and once the job has been invoiced we aim to land in front financially so that these projects can make a “contribution” to helping cover NGT’s general operating expenses and contribute towards our wider mission.

Q. Why not just set up a regular consulting business in the first place? Surely that would have been simpler?

I wish I had a dollar for every time I had been asked this question!

It is true that it would have been simpler, because setting up a charitable organisation carries many additional regulatory requirements (which is fair enough, to ensure we actually carry through on our purpose), in addition to those involved in running a regular business. For example, we are required to have our financial accounts and procedures independently audited every year for our annual report, and have to complete additional reporting to the ACNC, ASIC and REO, in addition to normal ATO GST reporting.

But if you are asking this question, then you may have missed the fact that NGT is about much more than just keeping people employed, paying the bills and delivering projects – as important as those things are to keeping the place running. For any non-government charitable organisation, it is what you choose to do with your discretionary time, resources and volunteer help that really counts. This is why you will now hear of “not-for-profit” organisations being more frequently described as “for purpose” instead.

We have ambitious goals to make a real difference to our community and environment that simply cannot be delivered through a regular (for profit) business model. The ability to use our expertise to independently identify, promote and deliver projects that need doing, with volunteer help (like the wetland restoration projects shown), funded by grants or donations is a big part of what we do.

Because of our overarching purpose, our consulting work sits seamlessly alongside these other objectives, allowing us to offer our expertise to assist others, while bringing in extra revenue to help run the broader organisation.

Q. Okay – so what makes NGT different to other environmental charities – don’t we have enough already?

There was a time maybe 15 years ago when I probably would have agreed with the premise of this question. Australia has a large number of charities and often their objectives seem to overlap. But the longer I have been involved one way or another in this sector – now up to 25 years – I have come to appreciate the need for diversity. It is essential.

The structure, history, purpose, culture, geographic and thematic scope of each organisation can vary significantly, and – despite the great work being done by all community groups and charities – these factors can inadvertently leave large gaps that are not being filled. Until you go specifically looking for those gaps, you may not even realise they exist, but I certainly started to appreciate them in my old job with the SA Government. For instance, I had ideas lined up for worthwhile restoration projects, but there was limited appetite (both within and outside government) to pursue them, so nothing would happen. Throw in artificial boundaries like state borders and, at times, things just became impossible!

So NGT was designed quite deliberately and strategically to fill the gaps we identified and to complement, rather than compete with, the good work of others.

Q. Is NGT just interested in wetlands?

Definitely not. They are very important to us, but wetlands are not all we do.

NGT ecological burn of habitat for the critically endangered plant – Cassinia tegulata – underway at Avenue.

Way back at the start when I was thinking about the design of NGT, on my checklist were things like:

- ensuring everything we do is underpinned by sound science

- having expertise in our team across a wide range of ecological disciplines

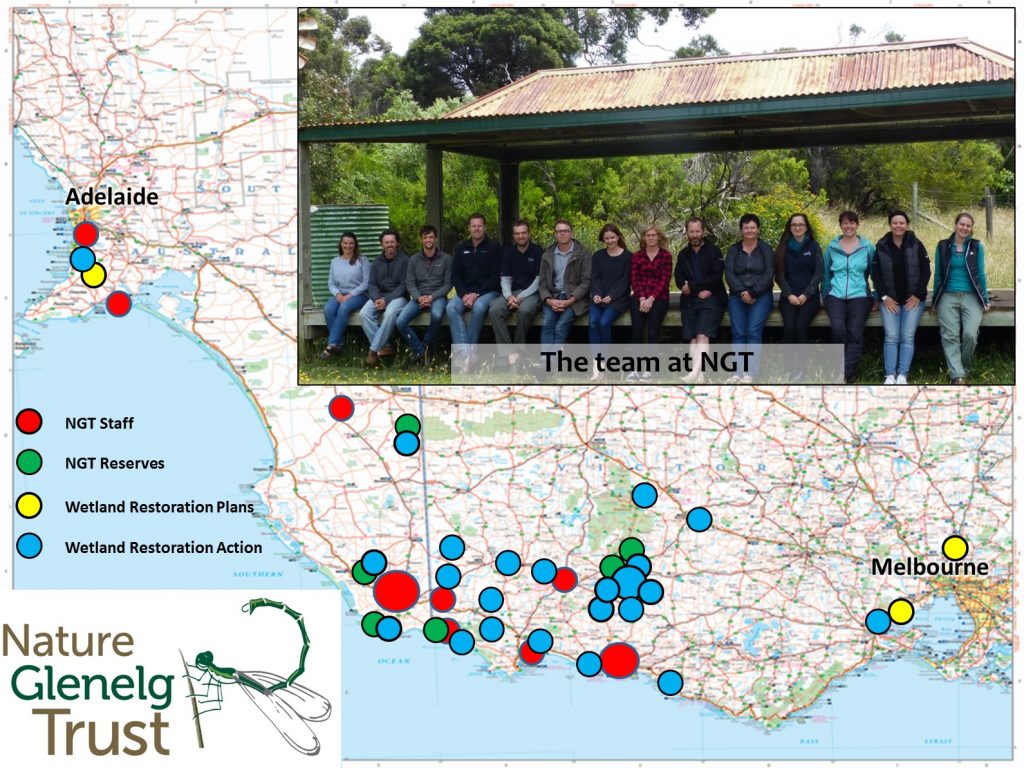

- having a decentralised workforce that covers a wide (but still broadly defined) geographic area, with staff able to work remotely

- working seamlessly across regions and borders

- having our heart and soul in the rural landscape

- being prepared to tackle anything worthwhile for biodiversity (especially difficult projects that others have no appetite for)

- being flexible, open-minded and filling gaps (making the most of being a young, small and nimble organisation)

- having a thematic focus to more actively promote that would set us apart from others (wetlands and aquatic species were an obvious choice in our core landscapes)

- giving donors the opportunity to experience and immerse themselves in the projects they support, by working in their comparative ‘backyard’ rather that somewhere they may never see or visit. Restoring the biodiversity of our temperate agricultural landscapes is so often overlooked!

The net effect of all this is that, by filling gaps, NGT has ended up becoming many different things to a wide range people in a variety of places, and we employ staff with very diverse ecological skills. Overall this means we tackle everything biodiversity related: for example, terrestrial and aquatic flora and fauna surveys, monitoring, research and ecology, threatened species management, environmental education, landscape assessment and restoration, to name a few. We also run a small nursery.

Q. The NGT model seems to work well. Can you come and work in our patch, because no one is doing what you do here?

This depends on where you are and what needs doing. Our main focal region is between Melbourne and Adelaide, where our staff and properties are located – but we also work in NSW and Tasmania on specific projects. Outside of our natural home in south-eastern Australia, requests for input or assistance further afield will still be assessed on a case by case basis – if we think we are genuinely the best option and can help. So don’t be shy – just ask!

We’re also happy to share our experiences with other people or groups who might like to experiment with replicating elements of our model in other parts of Australia. Every region is different, so locally designed solutions are always the best.

Not expanding also means that we can do our best to avoid the inevitable challenges that come with growing bigger, like how to protect our culture and keep our collegiate, informal atmosphere intact, plus how to maintain a flat outcome-focussed structure (i.e. to avoid having silos). At the moment, every single person at NGT is directly connected to our project work in a multitude of ways, myself included.

As an old friend of mine, Randall, used to say regularly when we worked together many years ago: “keep it real!”

Q. Why does NGT acquire land?

Sometimes a site comes along that has very special attributes or restoration potential, and the only way secure those outcomes is through land purchase. In some circumstances, this is literally the only way to resolve a difficult land management challenge – for example, where public conservation land tenure is fragmented, or, where a wetland or floodplain covers an entire parcel of land and restoration would render it uneconomic for the owner to keep farming it (see other examples below).

We didn’t specifically set out to become a large non-government conservation land owner (like the TLC, AWC or BHA – organisations I greatly admire!), but over time we’ve become custodians of several permanent reserves – each with their own unique attributes and challenges.

Ben from NGT preparing a water level sensor installation, in a restored Mount Burr Swamp – previously a cow paddock.

Something that does make us different to most other conservation organisations is that we’re taking on land that, for the most part (with a notable exception being Kurrawonga), is degraded from an environmental perspective, but has something special about it that makes restoration and permanent protection a smart idea. Whether that be restoring over 1000 acres of drained floodplain wetlands next the Grampians National Park with amazing educational potential, protecting the magnificent red gums of Long Point on the edge of Dunkeld, restoring wetlands adjacent to one of SA’s most bio-diverse reserves, or recovering vast woodlands near the western edge of the Little Desert National Park – these are all sites whose future trajectory would not have involved conservation if we hadn’t stepped in.

Most environmental scientists have been lecturing for decades about why we need to restore strategically located land for biodiversity in agricultural regions (where the trends for nature are not good), but very few people are tackling that challenge at scale – it is a big gap and we’re trying our very best to do something about it.

Hence another major objective in establishing our restoration reserves in particular, is to create demonstration sites, where we can share our experiences with the community and hopefully inspire others to follow suit. We know we can’t fix the landscape by ourselves!

Q. How does NGT pay for its land purchases?

The previous owners of Mt Burr Swamp, Helen and Neil Ellison, with Nature Glenelg Trust Manager Mark Bachmann (centre). The Ellisons made a range of concessions, including giving NGT extra time to secure funding over a period of four and a half years. The project wouldn’t have happened without their patience and support.

Through seeking grants, partnerships, donations and anything else we can think of! In some cases, because of the time fundraising can take, the previous owners have often been extremely patient with us.

A rare exception to this normal process is where some amazing people have simply gifted the land itself to NGT, for which we are just so grateful. The stories of Kurrawonga and Hutt Bay are beautiful examples of the type of generosity that exists in our community.

For straight purchases however, as you can imagine, financing the purchase of land that has often been ‘improved’ for farming in the agricultural zone, is problematic when the conservation dollar is already a scarce resource and there are so many worthwhile causes. Throw in the fact that the cost per hectare is far more than a bush block, the biodiversity values at the time of purchase are far less… maybe then you can appreciate why even the most strategically located potential restoration property next to a National Park usually just doesn’t have a chance. This is a hard sell!

So we have been quietly pursuing the type of projects that everyone agrees is a good idea, but no-one had previously worked out how to get off the ground. And yes, given a bit of time and adequate investment in restoration, we can turn things around pretty quickly.

As you’ll see in the next question, after purchase we are still charting a course forward and working out how to realise our vision for these areas…

Q. So NGT now owns all these properties, how do you intend to look after them?

Well that is an ongoing question that keeps me up at night!

Because of the way we started NGT, and a result of everything that has transpired since, we are now like your average farmer – asset rich but cash poor. But fear not, we have a plan…

Once we buy a property to restore, we have two big challenges.

The first is how to finance the restoration process itself, which involves things like removing drains, revegetation, reconfiguring fences and adjusting management regimes. Restoration costs can often be covered by grant funding, but grants that fit our specific circumstances can be infrequent – so timing is everything.

At a place like Walker Swamp, the stars miraculously aligned and we managed to secure a range of grants for on-ground works in perfect sequence, that allowed us to undertake major restoration works in relatively quick time (over a 2 year period). As a result, this property has now leaped ahead of some of our other reserves that we have actually owned for longer, in terms of its restoration trajectory. So there is an element of chance and opportunism involved, as we wait for the right opportunity to come along if relying on this type of investment.

The second challenge is even harder than the first: that is, how to cover the long-term, ongoing costs of managing these properties in perpetuity, well after the restoration works have been completed?

Our solution to that is the NGT Foundation – an endowment fund established by Nature Glenelg Trust where all donations contribute to a preserved capital balance (a Corpus fund), where only future interest or investment earnings will be used to help us cover our ongoing costs.

Please click here to learn more about the NGT Foundation.

Q. What can your supporters do to help NGT thrive?

I have three simple suggestions:

- To tell your friends to sign up to our newsletter and stay informed.

- To volunteer your time or come along to our events.

- To consider making small regular donations to our Foundation would also be marvellous.

But honestly and to close, just keep backing us in whatever way you can, and stay positive.

Collectively we are making a difference, and NGT wouldn’t be able to achieve any of this without you!

Mark Bachmann, 28th May 2020