Insights from the Freshwater Sciences 2023 conference, and Ayesha presents 20 years of Upper Hopkins salinity data

At the beginning of June, I headed to sunny Brisbane to attend Freshwater Sciences 2023. This was the combined annual conference of the Society for Freshwater Science, the Australian Freshwater Sciences Society and the New Zealand Freshwater Sciences Society, and the first time that all three groups had come together to host a conference. Nearly 800 people spent four days together, sharing outcomes from their research and monitoring programs from across the world.

Climate change and habitat loss were recurring themes in many of the talks. Researchers described the impact of changing conditions on their study systems, such as changing water regimes, warming water conditions, changing water chemistry, loss of riparian vegetation, and combinations of these factors. At times, the outlook appeared bleak.

However, a lot of organisations are actively working on restoration and mitigation. It was inspiring to hear about communities working together to improve water quality, reduce aquatic invasive species and recreate habitat. Importantly, scientists are thinking really carefully about the way they do their work so that it is planned for maximum benefit.

Three themes related to restoration emerged from the presentations I had the opportunity to listen to:

1. Variation across space and time

Nobody expects a freshwater system to be static. As we have all seen in our own local systems, wetlands and rivers change between seasons and among years, depending on such factors as annual rainfall or evaporation and longer-term changes in climate. This temporal variation is compounded with spatial variation: not all sites are the same! Freshwater systems differ among locations with different geology, different aquatic vegetation and different management histories, so we can’t expect them all to carry out the same ecological processes nor host the same fauna.

Throughout the conference, I heard researchers reporting how this variability is important and needs to be valued. Complexity builds resilience, and resilience increases biological diversity. Complexity occurs at multiple scales, from the microbial community that helps to decompose fallen leaf litter, to the diversity of cobbles in a riffle (rocks in a shallow fast flowing stream) that provide egg-laying sites for caddisflies, to the diversity of riparian vegetation or surrounding land use that modifies habitat availability and water quality for aquatic organisms.

2. Monitoring

Given all this variation over time and space, how do we best monitor our restoration efforts?

Many of the presentations that I saw from New Zealand and Australia discussed the challenge of effectively and efficiently sampling to monitor for changes following restoration. Changes may be subtle, and it may take many years for differences to become observable and measurable. Rather than waiting to see these changes, it may be smarter to monitor more broadly across many sites at various stages of restoration (and there were plenty of good statistical models to support this).

Australian ecologist, Ian Campbell, presented a “reflection and a rant” about monitoring river health. He was concerned that monitoring is generally being done poorly, and he reminded the audience that monitoring data needs to be properly (statistically) analysed for it to be useful. He succinctly summed up how we need to approach monitoring: We need to do more, we need to do it better, and it doesn’t need to cost more. This is an interesting challenge to those of us working in wetland restoration!

3. Community

An important part of attending large conferences like this is realising that there is a whole community of scientists and land managers working to understand their ecological system and how best to manage it. The conference opens the opportunity for scientists to work across disciplines and develop novel approaches to ecological problems.

One example of the importance of building a scientific community was a brilliant presentation about carbon in terrestrial and aquatic systems by two presenters from different research fields (Cry me a river: debating the importance of fresh waters in the global carbon cycle). Their presentation outlined their work with other collaborators that investigates microbial decomposition and how carbon moves through an ecosystem. It was wonderful to see the way these two presenters worked together in the presentation, and obviously they have a lot of other collaborations too (check out a their creative 5 min video on the importance of science communication).

Another part of community that was emphasised throughout the conference was the local and cultural communities. Many people working on restoration of wetlands and streams realised that they wanted to work with communities to ensure that everyone has a good understanding of their local freshwater system, and that community members can be engaged in the restoration activity and become good stewards of their site. For example, a lake monitoring program in Minnesota used citizen-collected data to monitor lakes in 33 watersheds – a project that would be too expensive to run by one organisation, but is possible (and powerful!) with the support of volunteers.

Importantly, the conference acknowledged Indigenous communities repeatedly over the four days of presentations. The conference began with a wonderful and generous Welcome to Country, and the conference was occasionally treated to Māori song (sometimes as part of a presentation, sometimes from the audience). My American friends were intrigued about the way we choose to recognise Traditional Owners; it’s not a widely adopted practice in the USA but maybe this will change in the future.

My presentation: EC monitoring in the Upper Hopkins

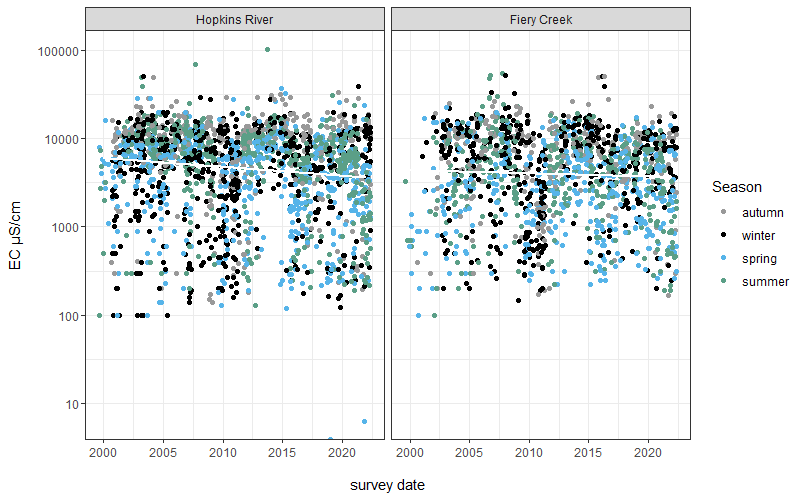

I presented a synthesis of 20 years of data collection by the Upper Hopkins Land Management Group (UHLMG) to monitor electrical conductivity (EC, a proxy measure for salinity) in rivers and creeks across the Upper Hopkins (approximately 70 sites). There is a lot of data after all of those years of collecting and I detected a very slight decline in EC levels over time. This may be due to changing land use or rainfall patterns, but I could not confirm this.

I also compared the EC data recorded by UHLMG to that recorded by the Bureau of Meteorology at the Wickliffe gauging station and found that they were quite similar. This shows that data collected by the community is accurate and can be extremely useful!