“Investing in Peatlands” – A new publication seeking to put peatlands on the agenda to protect the global climate, water and biodiversity

Back in September last year, we explained why NGT talks a lot about peatlands, because for those of us interested in peatlands, they can seem a bit like the perpetual ‘elephant in the room’. Why is this, you might ask?

Well, that is because for all the chatter that happens about developing environmental programs and policies for addressing risks to the climate, biodiversity and water resources (often separately I might add), peatlands almost always seem to get entirely overlooked, despite the fact that protecting and restoring peatlands directly addresses all three of these issues at once, in the same places.

In some ways this is understandable for a country like Australia, which at the continental scale is mostly arid, and yet around the damp temperate fringe – which overlaps with our most productive regions for agriculture – we do have peatlands. These peatlands are often small and patchily distributed, but – when you map them and add them all up (which is yet to comprehensively occur in many areas) – they tally up to a significant area that, as you will see below, well and truly punches above its weight.

It is worth noting that these special wetlands only occur in places where the hydrological conditions (usually underpinned by shallow groundwater) achieve year-round saturation of the ground. This in turn allows for rapid, continuous plant growth and the slow accumulation and preservation of organic material, as those plants drop endless amounts of leaves, branches and other organic material into the wet ground below.

As illustrated above, many of you may remember from your school days that peat is the first stage in the formation of many of the very fossil fuels that are now being extracted from deep underground, resulting in large amounts of additional carbon being released as they are burned. This takes slow-moving, stable carbon presently stored in the earth’s crust (the lithosphere) and adds it to the much faster-moving atmospheric carbon pool.

While planting trees is a worthwhile activity in its own right – and seems to get almost all the policy and media attention – it is worth considering that peatlands are nature’s genuinely sustainable solution for sequestering atmospheric carbon in a stable form, by literally burying the carbon back in the ground and onto a potential pathway to being locked back away from the atmospheric carbon cycle.

A peatland can achieve this, because it can keep growing and accumulating carbon, layer upon layer, over millennia, as long as its underlying hydrology remains intact. In contrast, the maximum amount of carbon able to be stored in a dryland forest or grassland within the terrestrial biosphere is usually limited by rainfall, and then remains available for potential release back to the atmospheric carbon cycle (through fire or decomposition). In a nutshell, most of this carbon is not on a path the re-enter the lithosphere one day in fossil form, because it is not in a location where it can be saturated, buried and preserved in the same way.

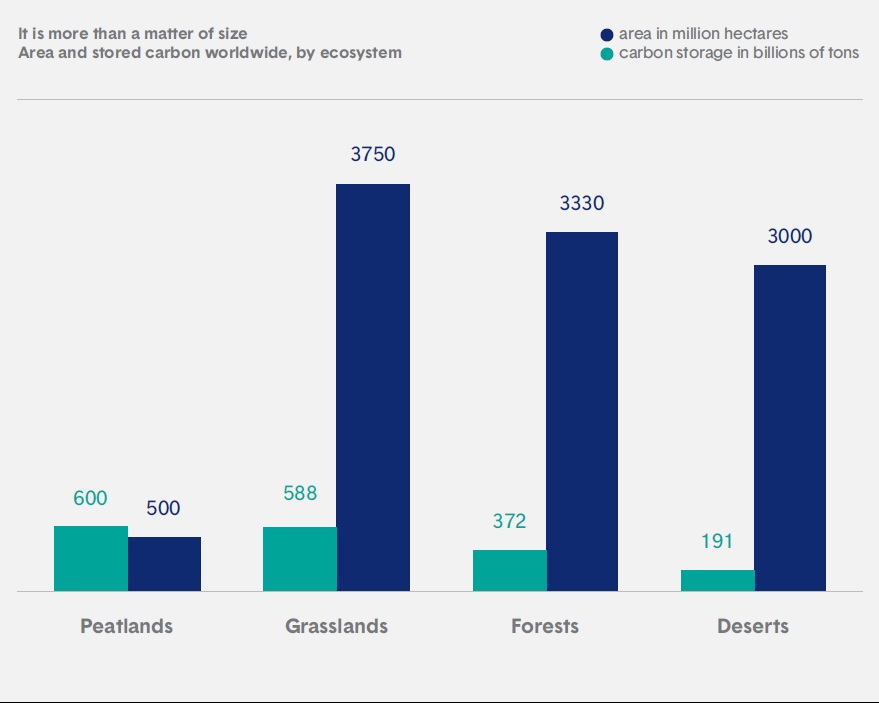

As shown in the diagram below, this is why peatlands – per unit of area – are so spatially efficient at accumulating and storing carbon. In fact, they are the largest global land-based ecosystem store of carbon, despite only covering 3% of the world’s surface.

With this backdrop in mind, it is great to be able to share a new publication by the Landscape Finance Lab and wide range of international partners – called “Investing in Peatlands“.

The report steps through everything you need to know about peatlands, and why they are a priority for investment in protection and restoration. It also openly shares one of the challenges for policy makers with restoring peatlands; namely, the initial spike in methane release that is often observed after a peatland is re-wetted. The diagram below explains the complicated short-term relationship for different greenhouse gas emissions observed at restored peatlands, a process that takes time to settle back to “normal” (i.e. similar to a natural, unmodified peatland) for a period after restoration.

Far from being a reason not to restore peatlands, this is a simply a reflection of the time it can take to reset any modified ecosystem and place it on a long-term trajectory of recovery (and, in this case, future carbon sequestration). The short-term metrics that are often used in carbon accounting for measuring success, need to get much better at accommodating the complexity of this part of the peatland restoration story. After all, we know that over the long-term peatlands successfully remove and accumulate large volumes of atmospheric carbon, or there simply would be no coal to dig out of the ground today!

To get into all the finer detail and learn more, you can download the pdf here, or read it in the viewer below.

As well as taking a look at the information above, you can read more about the background to the document here, and a copy of the launch webinar to promote “Investing in Peatlands” can be viewed below.

Finally, if you would like to make a donation support NGT’s work to restore peatlands across south-eastern Australia then please get in touch. We have a number of important peatland restoration projects under development in Victoria, South Australia and Tasmania that require additional investment, so if you are in a position to assist, we’d love to hear from you.