Mainland Forgotten Fauna: Part 5 – So, just how unique is Tasmania’s wildlife?

I’ve been lucky enough to head across Bass Straight to visit Tasmania a few times over the past 15 years and, as someone who has surveyed small mammals in the wild on the mainland since the mid-90s, the first thing that I notice is… you guessed it – the medium-sized mammals that litter the roadsides as roadkill!

The last time I was in Tasmania in March 2014, the very day we hopped off the boat, we came across a dead Southern Brown Bandicoot on the side of the road within an hour of leaving Devonport and heading inland. For comparison, in 20 years of driving around the bush in the South East of SA and western Victoria, I have only come across one roadkill Southern Brown Bandicoot – near Rennick in Victoria. Interestingly, I’ve actually found it much easier to spot these bandicoots on the mainland, when driving around far SW Western Australia on the couple of occasions I’ve been over there.

Anyway, I digress…

Back over in Tasmania, later on the same trip, one of the last things we saw as we travelled back from Hobart across the Island, was this Eastern Barred Bandicoot also struck by a car on a roadside.

My apologies if you are a bit squeamish, but us ‘mammal people’ find this type of thing very interesting to look at…!

Many local readers might immediately think “Victorian Volcanic Plains around Hamilton”, when thinking about this species – the last known places where records continued to trickle in over recent decades – although unfortunately the species is now considered extinct in the wild on the mainland.

Interestingly, this area is now what our collective social memory in this region still recognises as “Eastern Barred Bandicoot habitat” on the mainland.

But what if I told you that the species was also recorded in:

- Portland in 1854,

- Melbourne in 1886,

- the Tatiara (Upper South East of SA) in 1891,

- Mt Gambier in 1893, and

- near Warrnambool as late as the 1960s.

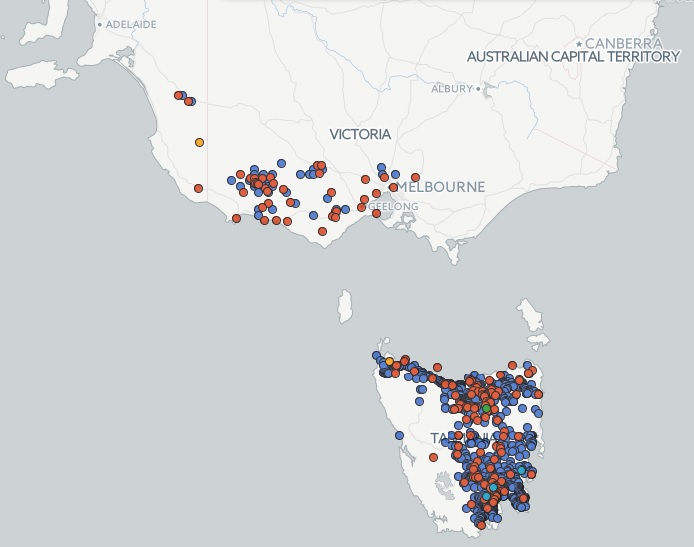

So the truth is that the early records we do have (noting that for species that disappeared long ago, this never represents the full extent of their original distribution) indicate that Eastern Barred Bandicoots probably occurred patchily across a portion of south-eastern Australia, equivalent to the size of Tasmania.

Not just the Hamilton tip – one of their last known mainland hideouts in the wild!

Oh, and by the way, both bandicoot species that we saw dead by the roadside in Tasmania were found in open farmland, nowhere near intact bushland, pristine grassland habitat or dense cover. Isn’t it interesting that we think of these species as being “habitat specialists” on the mainland?

I could also show maps similar to the above for a number of other species now lost from (or extremely rare on) the mainland, but still occurring in Tasmania.

Species like Tasmanian Pademelons and Tasmanian/Eastern Bettongs (but don’t let the “Tasmanian” bit mislead you!), Eastern Quolls and Tiger Quolls.

Tasmanian Pademelon, Tasmanian/Eastern Bettong and Eastern Quoll (again the number of Tasmanian records is biased by having a much longer recording period)

Do you, like me, ever question why we so easily now accept thinking of this wildlife (when we see it on the other side of Bass Straight) as being a uniquely “Tasmanian” fauna assemblage? It does seem odd when we know for a fact that all of these species were on the southern fringe of the mainland until just 120 years ago – the time when the dingo was lost from many districts and the fox ran rampant?

It also seems odd when we now know that these species play a crucial role in Tasmanian ecosystems – a function now missing from mainland habitats (sorry for those of you also interested in vegetation – that means there are no truly “in-tact, fully functional” grassland, woodland or forested habitats left in this part of the mainland!)

And so it turns out that a hunting trip through the depths of the Gippsland forests, the Otways, the Cobboboonee forest or the Grampians 120 years ago with your trusty shotgun, would have felt very much like being in the bush in most of Tasmania around the same time – albeit the productivity of the habitat in Tasmania might have meant the wildlife was a little more abundant, so you might have bagged a few more critters.

In fact, you would have encountered an almost identical suite of wildlife – with the only notable exceptions being the Devil and Thylacine – which as we’ve explained previously, were out-competed on the mainland by the dingo not long before Europeans arrived. However, now that the dingoes are all but gone from south-eastern Australia, they also might rightly be considered “mainland forgotten fauna”.

Clearly we have more to ponder!

In the next installment (part 6), despite being a sad topic, perhaps we should think a bit more about the mechanics of the small mammal community collapse – before future blogs investigate further what type of ecosystem this change has left behind, the “new nature” that we are familiar with on the mainland today.