My environmental journey and explaining why NGT exists…

In thinking about it afterwards, the CCSA awards evening and the philanthropy workshop last week brought together some ideas in a way that really struck a chord with me. The key one is just how important credibility is to the success of not-for-profit organisations and understanding the motivations and goals of the people that make them tick.

So although I do a lot of talking (I know… some of you are thinking, all the time!) about what NGT does, maybe it is time to share a little bit more of my personal story – to help explain why I do what I do.

Hopefully I can then encourage our staff to do the same thing over the months ahead – we’ll see!

As for me, I have never actually shared the details of my full journey with anyone I have worked with in the last 20 years (let alone a full-list of NGT newsletter subscribers!), so you can safely consider this story a once-off. OK – here we go…

My environmental journey

I never once went camping as a young child – in fact, like so many families both then and today, spending time in the bush just wasn’t something that we ever did (or even thought to do). Growing up in the western suburbs of Adelaide, the closest thing I could experience to a sense of being in nature as I got a bit older was riding my bike across to the Torrens River and following the linear park to the beach, where I would sit and watch the sunset, as pelicans would glide past. I can still imagine the balmy Adelaide evening breeze on my face and the serene sounds of the ocean, while the mayhem of suburbia played out behind me. Without realising it then, I can now see that I was yearning for experiences away from city life and the concrete jungle.

By the time I reached later teenage years, if I am honest, I was becoming disillusioned and angry, and the “fire in the belly” for environmental issues really started burning. This was mostly as a result of things I was seeing on the TV that I cared about, but had no control over or ability to influence – like the clearance of rainforest in Brazil or collusion of governments and multi-nationals to reap short-term profits at the expense of the long-term health and living conditions of third world villagers and their environment (think oil in the Niger Delta and the case of Ken Saro-Wiwa). In fact when I think of Ken Saro-Wiwa today and what he sacrificed for his beliefs – what was right – I still get fired up… things like this never leave you.

At that point I felt helpless, but perhaps I could channel my frustration by learning more about the environment at University? So I enrolled in a Conservation and Park Management Degree at the University of SA, back in the old days when there was still an outer-suburban campus with a country feel at Salisbury. I chose that degree because the University of Adelaide Degree at Roseworthy was even further from home – as it was, I spent 3 hours travelling on public transport every day for 3 years, to attend University at Salisbury.

I did well at school and could have chosen almost any so called ‘career path’, but I wasn’t interested in pursuing the well-known, highly esteemed professions simply because others thought they were important and paid well. I was more concerned about meeting my core objective of finding things to work on, if possible all the time, that I believed in. People around me then, even my parents, didn’t seem to fully grasp my motivations – but to their credit supported my choice despite not having any idea of what job I might do one day and whether I would be able to support myself.

Great lecturers at University (to name a few, people like Joan Gibbs, Roger Clay and Bob Baldock) opened my eyes (as a sheltered city kid) to the fact that an amazing wider, biodiverse world was out there to be discovered. Not just out there, but on our doorstep, and more importantly that there was plenty that needed doing. And then it dawned on me… perhaps there was something I could do after all with all that passion – the “fire in the belly” which was intensifying?

After an exploratory trip to the South East in spring 1996 with my beautiful (soon-to-be) wife Charlene (we met at University), later that year we made an offer to purchase our first bush block for conservation at Hatherleigh, while studying 2nd year of our degree. But being 19 years old and with a modest income from weekend shifts washing dishes at the Grand Hotel (at Glenelg), no bank would loan me the money required to settle, so my dad (Richard Bachmann) offered to be guarantor in case we failed to make repayments. Only then did I realise maybe my dad did understand my choices and what was motivating me. He was a quiet person, and because he passed away (at only 58) in 2002, that show of faith stills means a lot to me today.

After purchase, we placed the small 20 acre Hatherleigh property (on four titles), with threatened habitats at risk of being incrementally cleared through multiple rural living developments, under a Heritage Agreement to ensure the bulk of the site would be perpetually protected. Maybe not the smartest financial decision (so I was told many times over by various people), but I have always felt that if you want to be taken seriously in anything you do, then you have to “walk the talk” – staying true to your values and actually get things done.

Camping, cutting down pines and pulling boneseed, sitting by the campfire and the sights, sounds and smell of the bush – these early experiences are etched in my memory and – quite honestly – I was immediately hooked with a love of nature. Not on a screen or in a book – as had been the case so far – but real, intimately experienced nature. More importantly I had discovered something practical I could do, right here and now – I had found a positive outlet for my frustration.

Over subsequent years, as my income (and bank manager!) allowed, I have personally purchased and protected a further five bushland properties, having found myself in the right place at the right time to buy some amazing natural areas within my limited budget. These included 35 acres at Thornlea (1998), 200 acres at Strathdownie (2000), 300 acres at Lake Mundi (2007), 40 acres at Mumbannar (2007) and 250 acres at Greenwald (2008). Two of the properties (Hatherleigh and Thornlea) were later sold with permanent protection (Heritage Agreements) in place, to help fund subsequent (more strategic) purchases in 2007 and 2008. We still own and manage four bushland properties totalling 790 acres.

These are my sacred places, where I truly feel at one with myself and the world around me. These places are worth more to me than any material thing money could buy – justifying every cent it cost to secure them for conservation. So, if you are wondering why I drive a cheap, second hand car made in 1991 – well, now you know – I’d rather be paying off a loan to protect a bush block than go into debt to buy a newer car! And even though in recent years I don’t get to spend as much time out there as I would like to, with life’s other present demands, I have had wonderful support from committed people like Fred Aslin and his crew of helpers who have volunteered their time over the past 5 years to help me keep on top of pine wildlings. Thanks Fred!

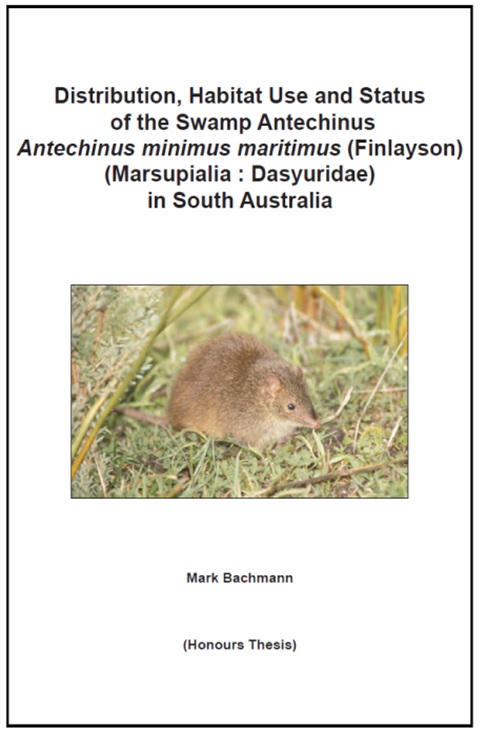

I completed my professional training by returning to the University of SA in 1999 (with supervisors Bob Sharrad and Fleur Tiver) to complete a first-class honours project researching the Swamp Antechinus (Antechinus minimus maritimus) in the South East – research that also helped consolidate the case for the purchase and creation of the first portion of what is now Lake St. Clair Conservation Park, near Robe. Truth be known, the reason I actually chose the species (after one of my long meandering conversations with then Robe-based Senior Ranger [and great down-to-earth bloke] Don Mount) is because I was hoping to influence the SA Government to buy the site from the farmer who was willing to sell. I got the qualification and the site was secured – a win-win and mission accomplished!

We moved to the South East in mid-1999 and have lived in the region ever since, having been fortunate enough to find environmental work, which made it possible to relocate – first to Robe with National Parks and then Mt Gambier, where I started as the South East’s first Regional Ecologist in December 1999.

And that was my real lucky break. Not only did I start working for one of the nicest people you could hope to meet, Brenton Grear (now Regional Director with DEWNR in the AMLR), but being a new role, I was given a lot of scope to learn on the job and make the role my own. The best thing about this experience is that I got to practice being creative (I learned how to come up with an idea, develop it, navigate the bureaucracy and see it through) and I also gained the confidence to use my expertise to fight for what was right; whether that be (for just a couple of examples) setting up the regional threatened species program or pursuing the purchase and restoration of Pick Swamp, or taking a stand from “within the system” by appearing before two SA Parliamentary Committee hearings to calmly and rationally state the case against proceeding with deep drainage of the West Avenue Range Watercourse in the Upper South East. While this ultimately failed to achieve the right result for the environment (to my great despair at the time), I am proud to say that I upheld the core principles of working in the public service, which are to provide frank and fearless advice to the government of the day, so that all decisions are made in full awareness of the facts and the likely repercussions.

So somehow I got lucky… I landed in two roles over 12 years (perhaps now much rarer in government) where my personal beliefs and professional requirements of the job allowed me to not treat work simply as work, but as a vocation or calling. The downside however (yes there is a downside!) is that it becomes very difficult to put boundaries around the hours you are prepared to invest in what you do, particularly when it becomes clear that the really significant projects (like Pick Swamp and, more recently with NGT, Mt Burr Swamp for example) wouldn’t happen within the constraints of working a regular 9 to 5 job – these are optional extra (high risk – i.e. likely to fail) projects that no-one in their right mind would ask you to do, so they can literally only happen if you are prepared to put in time ‘over and above’ the regular work that needs doing.

As you have probably gathered by reading this far, I don’t do what I do simply to work and earn money – this is not ‘just a job’. But because we live in an era where it is possible to work on environmental issues as a paid profession, this means I have been able to fully commit myself to achieving results for the environment – all day, every day – without having to worry about holding down another job that I’m not emotionally invested in. This simply wasn’t possible for committed pioneer field naturalists 50 years ago, who were restricted to spending only limited time after hours on the causes they cared about, while they worked in other professions to pay their bills. Indeed for most people and their personal interests in our society, this is still true today.

But with the privilege of this being both a paid profession and a personal passion, comes great responsibility. This is why I have always been prepared to take a chance by investing additional (hence always unpaid) time in ideas that may seem unrealistic or ambitious (and the risk of making mistakes that comes with that). While often those ideas have failed over the years, occasionally they have worked, and when they do it lifts everyone’s spirits. I truly believe we need big ideas and hard-fought wins to keep us motivated.

However after 12 years, I eventually reached a point where I felt that I could be more effective by leaving government, despite having a permanent job and working closely over the years with a number of really great people within government. I especially wanted to see what had been achieved at Pick Swamp replicated elsewhere – including western Victoria where so much wetland restoration potential exists. To name just a few people who really inspired me over my time with the SA Government, outside of some great individuals I worked with in the regional office in Mt Gambier (too many to name!), were/are people like Jason van Weenen and Peter Copley in Adelaide, Geoff Axford in the Outback, David Taylor on Kangaroo Island and Allan Holmes (who made the big call and backed the purchase of Pick Swamp at a crucial moment in 2005).

The Original NGT Committee of Management:

From Left to Right: Nick Whiterod, Michael Hammer, (former member) Becky McCann, Lachlan Farrington, Melissa Herpich, Cath Dickson, Mark Bachmann

So, I quietly tapped several trusted colleagues on the shoulder in mid-2011 and, after an intensive 6 month period of behind the scenes preparation, NGT was launched on the 16th of January 2012, as a cross-regional, cross-border NGO, with an emphasis on wetlands enshrined in the organisation’s charter. As you have probably come to know, NGT has been busy ever since trying to get things done on the ground.

I guess you could say, as captured in the blogs on this website, the rest is history! We’ve worked extremely hard, taken chances, had a number of great successes and yes, also made a few mistakes – but in my view everyone in our team is giving this ongoing experiment their very best shot – and I thank them deeply for showing that level of commitment.

In case you are wondering, I am still passionate and motivated by the idea that we can all make a difference – either dreaming up big ideas and then finding a way to make them happen, or supporting those that do. For NGT that has meant doing practical things like: working with some of our wonderful farmers across this region to restore some of their best private wetlands; partnering with government to protect and restore habitat for threatened species; and, providing the community with the opportunity to chip in and help NGT purchase and restore Mt Burr Swamp – just to name a few examples.

Taking the time to get to know and listen to people on the land (an incredible yet undervalued regional asset) and finding common ground, discovering and understanding our history (the good, bad and ugly) and sharing meaningful stories that connect people to nature are just some of the key ingredients that occasionally help us to achieve success against the odds.

So there is no need to feel helpless as I did 20 years ago, because this is our patch and we have proven that with hard work (and an occasional dose of luck!) we can make good things happen where it counts – in our own ‘backyard’.