Sharing some fascinating old and new perspectives on Long Swamp

It is time to share a couple of fascinating, but vastly different perspectives on the award winning Long Swamp Restoration Project – now that the restoration works are complete. One perspective is from the sky, and the other is from the past.

Firstly, let’s go back in time…

“he went along one day and it was sort of trickling over the edge of the bank, and he just dragged a little track with the trap hoe and it started to run, and eventually it formed a creek – oh, maybe 10 yards wide and 6 or 8 inches deep, and it ran there for years”

These are the words of Jack Kerr, son of Ken Kerr, recalling how his father opened up the ocean outlet from Long Swamp at Nobles Rocks in the 1930s, when being interviewed by Portland historian Garry Kerr. You can hear Jack speak about this in a video posted by Garry Kerr, around the 15 minute mark. Suddenly, we have this fresh account of a distant time that really brought a key event in the Long Swamp story back to life.

Garry very kindly subsequently arranged for me to meet Jack (who is now in his 90s) late last year and it was fantastic to have the opportunity to ask him about his life at Winnap, and his boyhood memories of his father’s coastal block before it was sold and planted to pines in the 1940s.

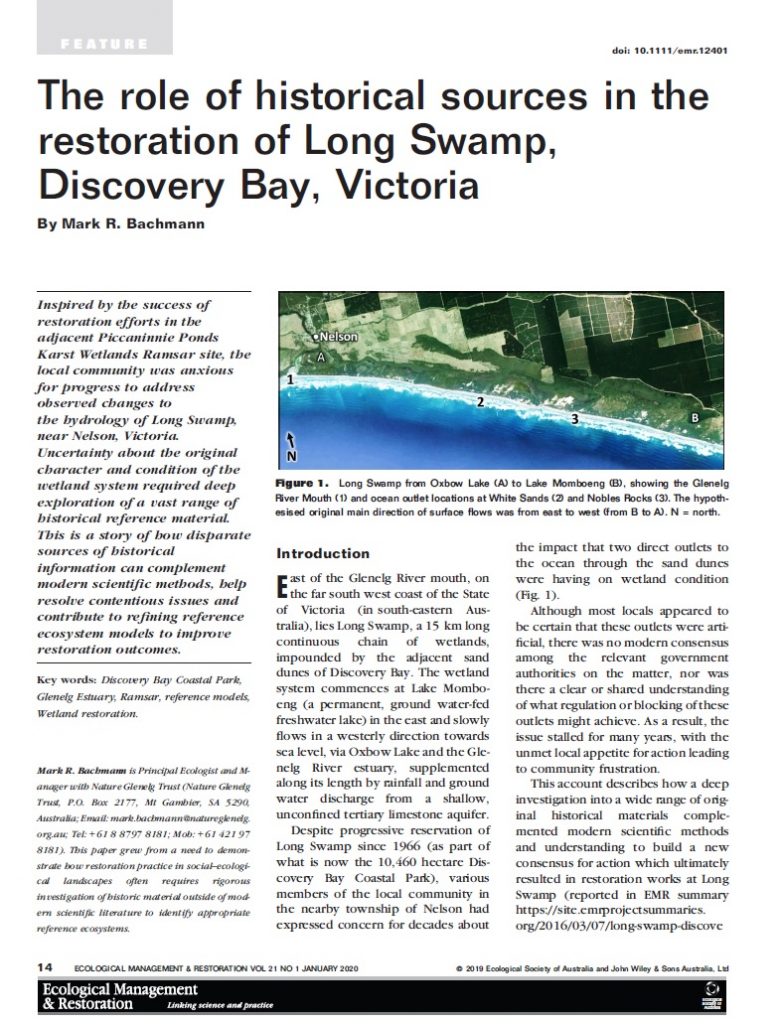

Around the same time last year, I was fortunate to receive an invitation to write a feature article about the Long Swamp Restoration Project for the journal Ecological Management and Restoration (EMR). This gave me the opportunity to properly document the whole (rather complicated!) story of how historic information sources played a critical role in forming our goals for the project, and how this information (including Jack’s observations and some other new insights) now underpins our modern understanding of site hydrology.

If you are interested to read more about this story, and the unique perspective on Long Swamp that emerged as a result, the full article can be downloaded here, or viewed below at the end of this article.

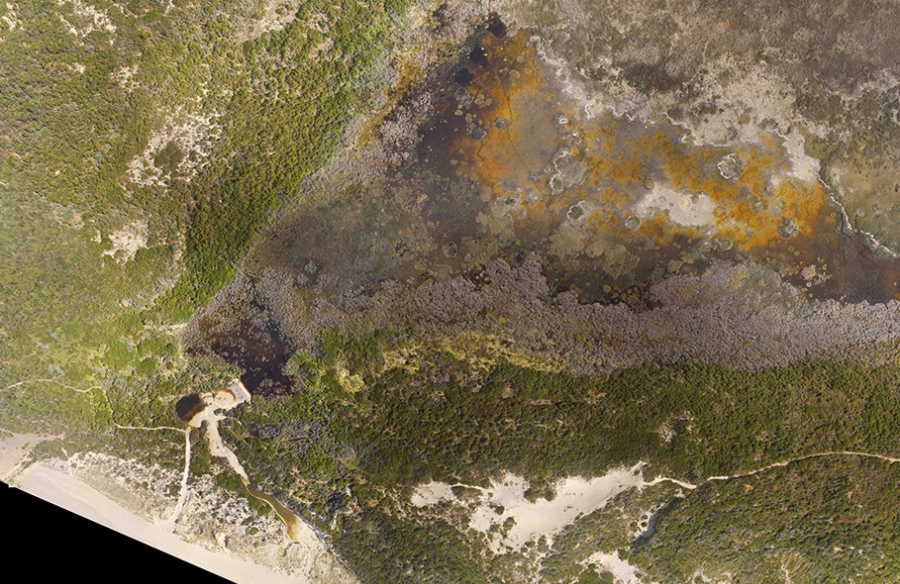

Secondly, let’s fast forward to the results of the project today, and have a look at the changing ‘birds eye view’ of Bully Lake, the restored coastal permanent wetland within Long Swamp near Nobles Rocks.

As you will learn if you read the article referred to above, Bully Lake had become the ‘forgotten wetland’ of Long Swamp, lost from local memory since the modern outlet drain (which eventually became deeply eroded) was first cut by Ken Kerr in the 1930s. Draining the lake directly to the sea turned it into a much drier, seasonal wetland, and caused a series of ecological knock-on effects for the lake, Long Swamp and the Glenelg River estuary more broadly. However, the reversal of some of these changes at Bully Lake itself are now clearly visible since restoration work commenced:

There is a lot to study in these 3 images, but to summarise, the main changes can be seen in:

- the artificial outlet drain itself (in the lower left corner of the image), and

- the appearance of Bully Lake, which shows spontaneous recovery of permanent aquatic habitats (note the changes in colour and texture – middle to top right of each image) in response to our restoration works in the outlet drain.

Bully Lake has now become a regular place for sightings of the nationally endangered Australasian Bittern, among a wide range of other species which are taking advantage of the improvement in wetland condition in Long Swamp, including nationally threatened freshwater fish.

In the final image, a small amount of seepage is still visible in a couple of remaining sections of the former channel, but this no longer breaches the berm of deposited sand on the beach and we now expect the natural process of primary dune formation to eventually seal up the remainder of the old outlet opening on the coast, which has been present at this location since it was cut in the mid-1930s. We also expect coastal native vegetation to rapidly colonise and stabilise the new sand dune and infilled sections of former channel, helping to consolidate and permanently secure the outcomes of this important project.

Our long term goal – which the natural, low-impact methods we’ve employed will ultimately allow us to realise – is simply for the evidence of the works to gradually disappear, as the restored wetlands bounce back and nature slowly reclaims this stretch of wild and beautiful coast.

Nature Glenelg Trust has undertaken works to permanently restore of Long Swamp with grant funding provided by the Victorian Government Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning. We are also grateful for ongoing support from the Gunditj Mirring Traditional Owner Aboriginal Corporation, Parks Victoria, the Glenelg Hopkins CMA, the Nelson Coast Care Group and other community groups.