Species of the month: Orange-bellied Parrot

You’ve probably heard of the Orange-bellied Parrot (Neophema chrysogaster) and might be familiar with some or even a lot of this species’ story. Over the past few years we’ve written several posts about the OBP, but I thought it was time to refresh your memory with a more detailed overview of this elusive bird.

The Orange-bellied Parrot (or OBP for short) is an Australian migratory, ground-dwelling parrot that splits its time between south-western Tasmania and south-eastern mainland Australia (note: you can learn more about migratory birds from NGT here). It is listed as a Critically Endangered species under the Federal Environmental Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999, and as a threatened species in NSW, Vic, Tasmania and SA.

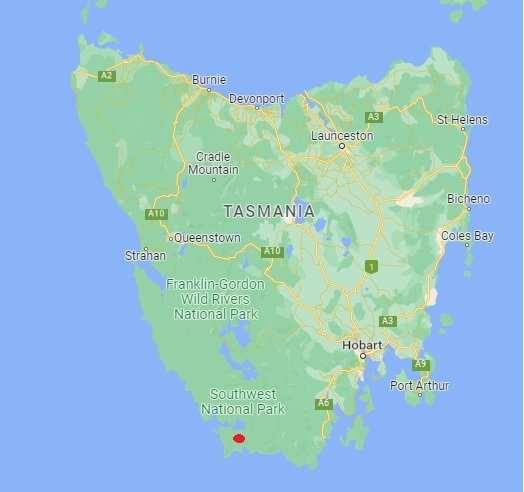

Over summer, OBPs can be found around Melaleuca, Tasmania, where the species breeds in the tall wet eucalypt forests and feeds in the buttongrass and sedgeland plains. During this time the OBP Tasmanian Program conducts a census at the start of each breeding season, provides supplementary food at feed tables, monitors nests, and bands fledglings before their migration. As OBPs nest in hollows, nest boxes have been supplied by the OBP Tasmanian Program to assist with nesting.

Historically, the breeding range of OBPs extended along the western and southern coasts and east toward the Southport region of Tasmania. But the current breeding range is restricted to within 20 kilometres of Melaleuca.

Food plants at Melaleuca include the mature flowers, fruits and seeds of a range of grasses, chenopods, sedges and herbs. As changes in vegetation structure, plant species diversity and seeding response to fire has influenced the distribution and abundance of naturally available food species, supplementary food is also supplied at feed tables. The feed tables also aid in conducting the census, where individual birds’ leg bands are recorded each day until the census date. Each bird must be sighted twice to be counted in the census and remove any mis-readings. Seventy OBPs were confirmed during the 2021 census, the highest number of OBPs confirmed in at least 15 years!

During the 2021/22 breeding season a number of OBPs were not seen later in the breeding season, and the reason is still unknown. One possible theory is that OBPs have moved further into the historical breeding and feeding range after a planned burn in the area. As each bird is banded and recorded by the OBP Tasmanian Program, sightings of these birds on the mainland over winter or again at Melaleuca in spring/summer will help provide some answers to these missing birds. Similarly, if an unbanded juvenile OBP is sighted on the mainland over winter, it will confirm that OBPs have successfully bred outside the monitored 20 kilometre area around Melaleuca. If it were to occur, this would be a very exciting discovery.

As a result of numbers reaching critically low levels in the wild, OBPs are now also captivity bred and released to supplement the wild population and boost breeding and fledgling success. OBPs are released in spring and autumn at both Melaleuca and on the mainland. Before being released, birds are screen by veterinarians for disease and pathogens. All wild nestlings are also tested for beak and feather disease virus to monitor the prevalence and impact of this virus on the wild population. After the autumn release at Melaleuca it was expected that 140 birds would migrate to the mainland.

From about late March into April, OBPs fly north across Bass Strait to the mainland where they spend winter feeding on saltmarsh. During this flight they island hop, with individual birds being observed feeding for days, sometimes weeks on Robbins, Perkins, Montague, Hunter and King Islands.

Although historically covering more of the coast to the east and west, their current mainland distribution is within 10 kilometres of the coast from Gippsland, Victoria to the Murray River Mouth in South Australia. OBPs feed on a variety of native and introduced species including beaded glasswort (Sarcocornia qinqueflora), fat hen (Chenopodium glaucum), goosefoot (Chenopodium album), and pasture grasses. They prefer habitat that includes rushes and sedges to enable them to hide if scared, as well as taller trees to roost during the middle of the day and overnight. You can watch a video on preferred habitat here. Habitat degradation is thought to be the primary threat to OBPs.

During the winter months, volunteers across south-eastern Australia spend time in saltmarsh habitat looking for OBPs. Sightings are reported to the National Recovery Team, and if leg bands are able to be read, details such as age and whether the bird was wild reared or captive-bred are relayed back to volunteers. Sightings of OBPs by volunteers also help identify where habitat protection and feral predator control may be needed. This winter season will also hopefully provide some answers as to what happened to some of the birds that ‘disappeared’ from Melaleuca during the summer breeding season. So it is an important year for the species on the mainland!

There are three official survey weekends throughout the mainland season, the first of which was held in May, with two upcoming surveys on 23-24 July and 10-11 September. Surveys are also undertaken every other day during winter. The best time to look for OBPs is from dawn until 11am, then from 2pm until dusk, as they like a siesta in the middle of the day.

OBPs migrate back to Melaleuca from late September. It is thought they take advantage of north-westerly winds, arriving in waves, sometimes completing the flight in less than two days. Older birds are the first to arrive at Melaleuca, followed by the first year birds in October to mid-November.

OBPs look very similar to three other Neophema species, the Rock Parrot, Elegant Parrot and Blue Wing Parrot. To make it even trickier, just because it has an orange belly doesn’t make it an OBP, and OBPs are often seen with flocks of these species. To help you identify OBPs, check out the video below which was created by NGT’s Nicole a couple of years ago. We’ve also linked a brochure which may be handy in the field (you can read it below too).

If you would like to volunteer in the winter search for OBPs in Victoria please get in touch with Jess via the email below.

The OBP project is supported by Glenelg Hopkins CMA and the Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning through funding from the Australian Government’s National Landcare Program.