Let’s go back to the convict days in Tasmania to untangle the early drainage history of Burdens Marsh

As we’ve shared in recent months, NGT is delighted to be working again with the Tasmanian Land Conservancy (TLC), undertaking an eco-hydrological assessment of Burdens Marsh, a highly significant but modified wetland area that lies within the TLC’s Sloping Main Reserve on the Tasman Peninsula.

One of the tasks that we tackle early in the process of getting to know a site, is mapping all the current observable changes to site topography and drainage, informed by a combination of aerial photography (which is usually available over time back to the 1940s), modern LiDAR data (which accurately shows us terrain), and an on-site assessment. This is the first step in understanding and documenting what physical modifications have occurred at a site during past land use, so that we can then work out exactly why these works were done – in terms of what land management outcome was sought. This not only helps us describe the trend of ecological change at a site, but it also often gives us clues as to the likely remedial works required to set a site back on a trajectory of ecological improvement and/or recovery.

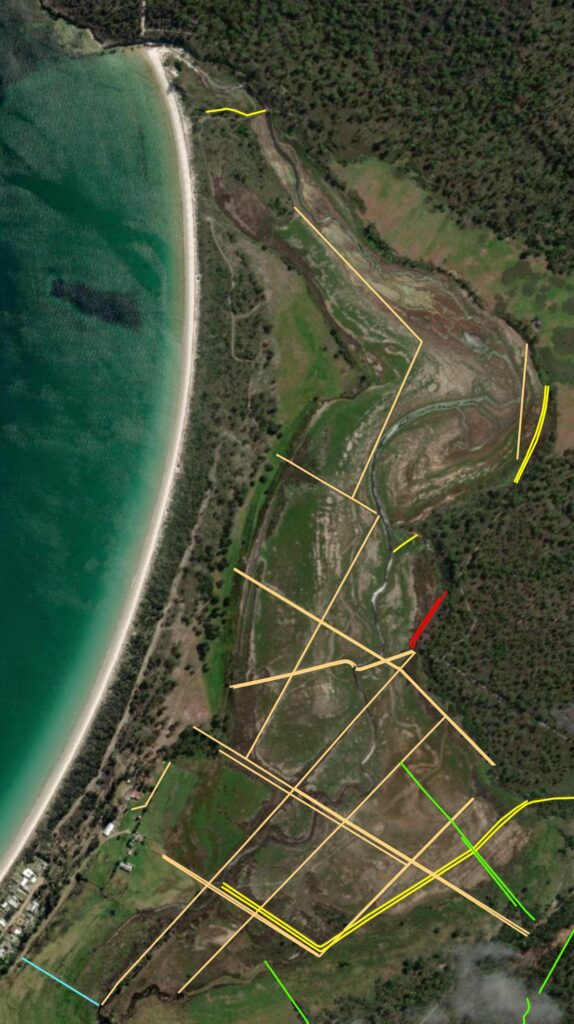

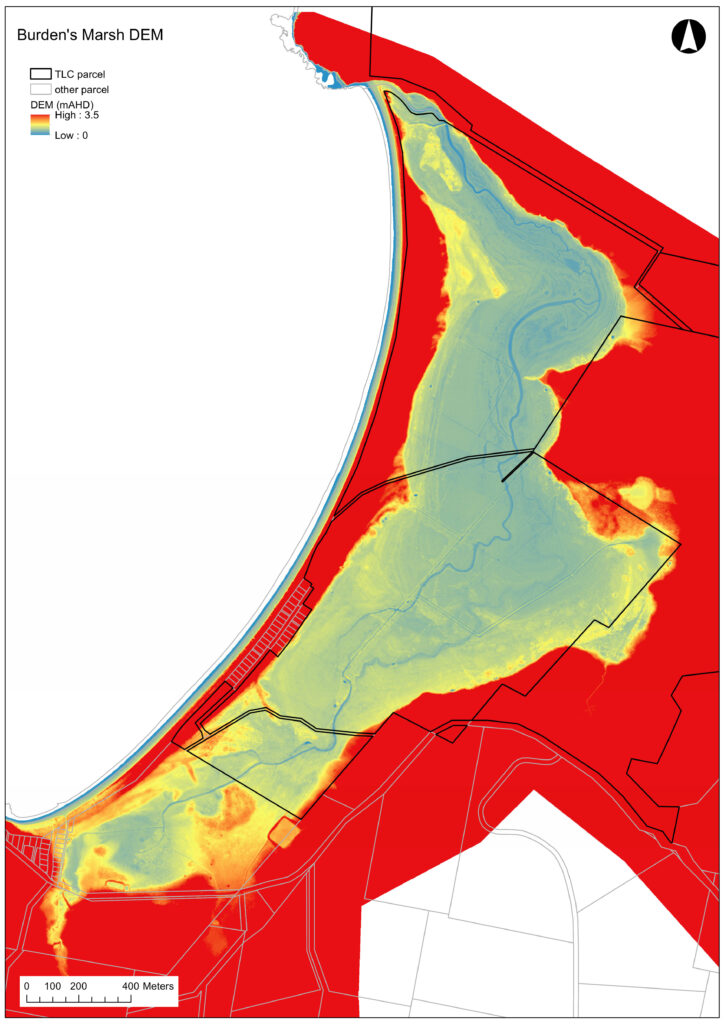

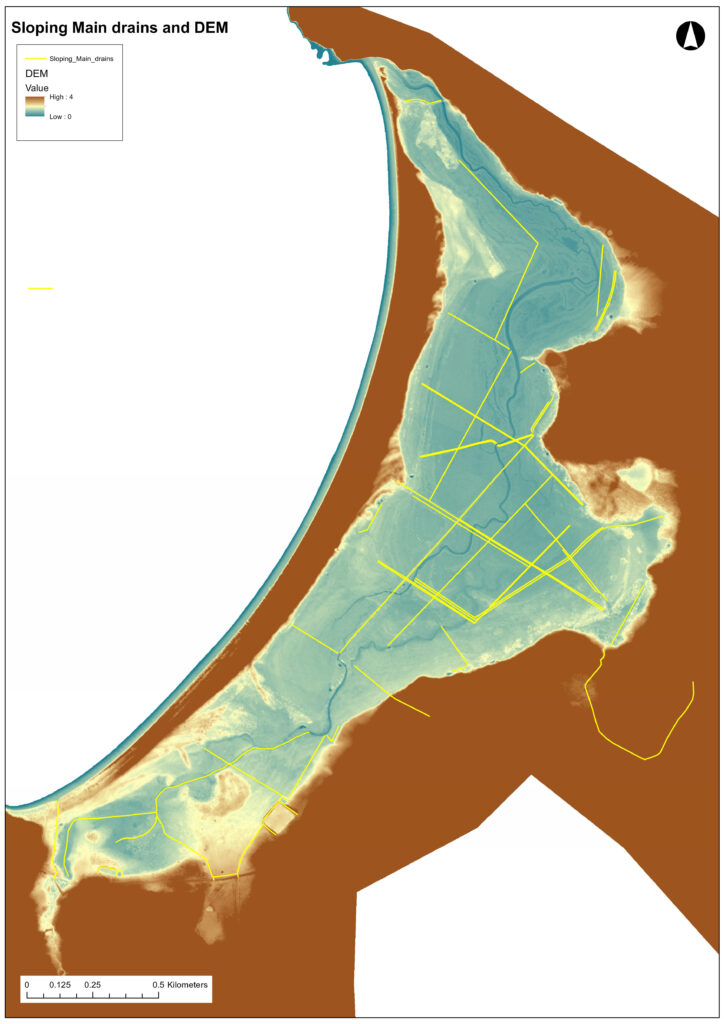

Although we shared some of this work at Burdens Marsh previously, including a map of changes to drainage over time in the most recent update from October, we have provided a more complete picture below. On the left is the raw Digital Elevation Model (DEM) based on LiDAR, while the centre image shows the locations of drains and embankments mapped in yellow, based on features visible in the DEM, and right shows how these features were classified after closer analysis of the aerial photographic record over time, and after ground-truthing of all features during a site visit by Ben and Bec.

Any features that have been created or modified since the aerial photographic record began, and can therefore be more accurately dated, are highlighted by the bright colours (excluding beige/brown) in the image above right (specifically: blue, green, yellow, red, purple).

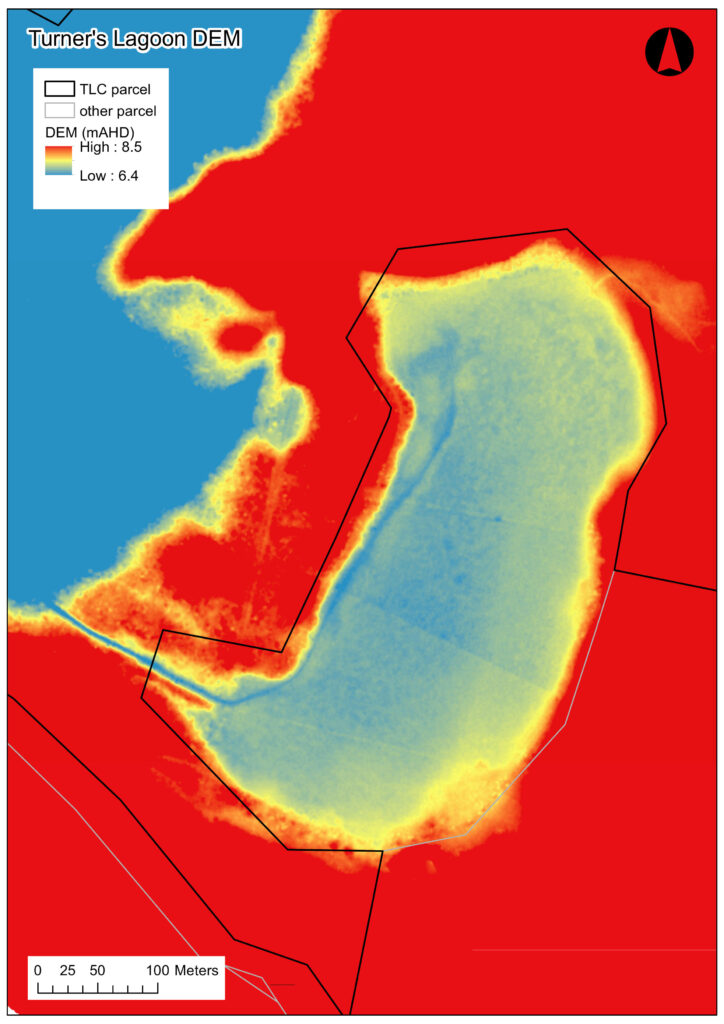

A good example to show how this type of change can be detected in the aerial photographic record, and supported by the DEM, is Turners Lagoon.

Turners Lagoon is situated on Crown Land and is surrounded by the eastern flank of Sloping Main Reserve, wrapping around 3/4 of its boundary. As you will see in the image below, in 1946 this wetland was not artificially drained and was full of water.

Indeed, in a recent discussion with John Price (the previous owner of Burdens Marsh), he recalled that before it was artificially drained, Turners Lagoon was quite a deep wetland, that could fill to up to 6 foot in depth, or ‘above his head’. This wetland is visible as being artificially drained for the first time in the 1975 aerial image, and this major artificial cutting also very clearly shows up in the DEM, as shown above.

We are very fortunate that John Price (who has lived at Slopen Main ever since his family purchased the property in the 1920s), has detailed knowledge of the management changes that have occurred on and around the property, that can be matched against and/or sit alongside the aerial photographic record since the 1940s. This puts us in a very privileged position for access to local knowledge that covers all the relevant recent site history.

But what about disentangling the history of change before that time?

In contrast, the cluster of light brown/beige lines on the map of Sloping Main above, also shown here closer up, are a notable exception to the more accurate dating we can achieve for works that have occurred since the 1940s. These works were already present in the first aerial images, so we simply know they existed before 1946.

John Price recalled they were long in place when the Price family purchased the property in the 1920s, and it was common local knowledge that these early features through the main saltmarsh area are much older, dating back to the convict era.

For piecing together the early history of Burdens Marsh, to help us disentangle these very old drains and embankments from the rest of the story, we are very fortunate to have access to a couple of fantastic resources, to complement John Price’s intimate local knowledge:

(1) a 2007 book called ‘Probation in Paradise’, written by John Thompson, which documents the convict story of the Tasman Peninsula – including the Slopen/Sloping Main area in great detail, and

(2) a set of more recent notes compiled this year (2023) by Malcolm Ward for the TLC on the early European history of Sloping Main.

I have also found some early newspaper references that help fill in key gaps (as indicated below).

We’ll take a closer look at some of the early maps next time, but in very broad detail (and subject to review as more detail emerges), together these references to the early history of Burdens Marsh give us the following preliminary timeline of occupation and development:

- Pre-European arrival: The site was home to the Pydairrerme (Tasman Peninsula) clan of the Paredarerme (Oyster Bay) nation.

- Late 1820s: Establishment of a 300 acre farm by Joseph Tice Gellibrand at Sloping Main

- 1830: The Port Arthur penal settlement begins, leading to the eventual eviction of all settlers from the Tasman Peninsula

- c. 1833: Despite the instruction for settlers to leave, Gellibrand is still occupying land at Sloping Main with cattle loose on the Peninsula. Gellibrand seeks a new, larger land grant elsewhere as compensation for vacating Sloping Main, and values his improvements at £1000. These:

“improvements consisted in draining a saltwater marsh, fencing, ploughing,

and building house, barns and stockyards”

(Archives quoted in the Hobart Critic, 21st April 1923)

- By 1836: the buildings and other infrastructure built by Gellibrand have been taken over the by the military, and improved for their purposes. The plans they drew of some of the buildings in 1836 are shown above. It is hypothesised by John Thompson in his 2007 book that Gellibrand’s original house may have been modified, doubling its size by the time these plans were drawn. This would explain why the timber slats on the building don’t match, with one half horizontal and the other vertical and no centre door connecting to two halves, suggesting the building was erected in two stages.

- By 1840: there was a route established/utilised across Burdens Marsh between a constable station near the beach at Sloping Main and the coal mines near Salem Bay.

- From 1830s – 1870s: Port Arthur Penal settlement results in farming taking place within Burdens Marsh, where Gellibrand had farmed. Maintenance and/or expansion of Gellibrand’s original drainage scheme is highly likely to have occurred during this period.

- 1877: Port Arthur closes down, and settlement recommences across the Tasman Peninsula.

- 1891: Jacob Burden purchases the ‘Slopen Main’ property, which includes the bulk of Burdens Marsh.

- 1913: William McWilliams puchases the property from Jacob Burden

- 1920s: John Athol Price (John’s father) and his brother Eric purchase land at Sloping Main

In summary, and consistent with a pattern we have seen in other areas along Tasmania’s east coast, it seems highly likely that Joseph Gellibrand specifically targeted Burdens Marsh when he first selected land there – not only were swamps favoured for grazing, but there was the potential to more quickly and easily improve its grazing potential through artificial drainage. This was also usually a more efficient way to develop a larger area of land than via the physical clearing of other more densely vegetated land, which at that time was all done by hand.

With convict labour available and the concept of land drainage fresh in the settlers’ minds from experiences of developments underway back in England (and Europe more broadly), this activity appears to have taken place at Burdens Marsh in the late 1820s. Ironically a short time later, from the 1830s and beyond, convicts were active in the very same area after the establishment of the Port Arthur Penal Colony, which makes it highly likely that these works were maintained and expanded over subsequent decades, leaving us with the legacy of artificial drainage that then first appears in the 1946 aerial photograph.

The intent, function, design and impact of the works, incorporating an analysis of the early maps, is a topic we will address next month. But for now, and needless to say, the legacy of Joseph Gellibrand’s original drainage scheme, and the convict farming enterprise that followed him, is still very much visible and evident at Burdens Marsh today!

This project is being delivered by NGT in partnership with the Tasmanian Land Conservancy,

with support from the Purryburry Trust