Tasmania’s convict past and saltmarsh remediation works collide at Long Point, Moulting Lagoon

As a further sequel to last month’s story about the commencement of saltmarsh restoration works adjacent to the Moulting Lagoon Ramsar site at Yard’s Hole, this month we’re taking a look at the early works completed next door at Long Point, a Tasmanian Land Conservancy reserve, which is also adjacent to Moulting Lagoon and contains some of the east coast’s most important saltmarsh habitat.

The convict past and land management impacts at Long Point

While unfortunately we won’t have the time to complete the level of in-depth research required to fully explore the early European occupation and colonial history of the site, we do know one important fact that emerged from that period – i.e. convict works completed at that time had a big impact on land management, especially the hydrology of the site, which has continued to influence its ecology until the present day. That is because this early colonial period resulted in the construction of a system of levee embankments across and around the saltmarsh at Long Point totalling about 2.4 km in length, as we explored in this story last year.

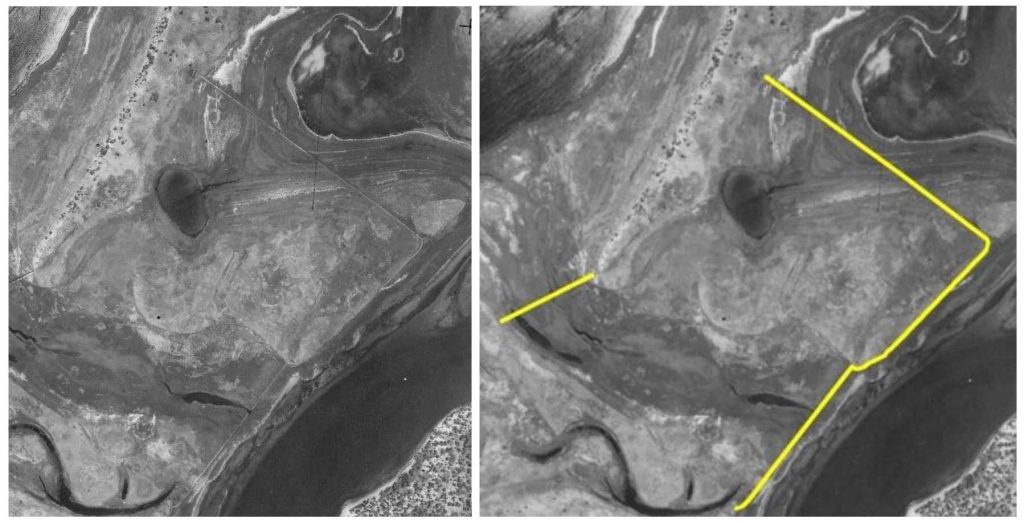

These levee banks are shown below.

While we have so far not come across any specific reference to exact timing of construction, our current best estimate is that these levee banks are likely to be approximately 180-190 years old, having been constructed by hand using convict labour sometime between 1825 and 1850. Deeper exploration of early records may be able to shed light on the precise timing.

This current estimate is based on the fact that:

- The British Government transported about 76,000 convicts to Tasmania between 1804 and 1853.

- Convict work gangs were commonly made available during this period and dispersed across Tasmania to undertake work improving the agricultural production capacity of land occupied by settlers.

- For example, George Meredith, who was one of the first settlers to arrive and take up land in the central east coast in 1821, was known to utilise convict labour. He occupied vast amounts of land around Moulting Lagoon near present day Swansea around the Aspley and Swan Rivers, including areas that he was never formally granted by the colonial government.

- Whether it was George Meredith, or another early colonial-era settler, the works were completed at a similar time to when the Aspley Marshes were also drained.

At the same time as broadly honing in on when the levee banks were constructed, we have also been able to more clearly ascertain their intent.

As shown in the image above, we have been able to demonstrate that the embankments at Long Point were an attempt at early saltmarsh reclamation works, presumably to improve the reliability of this area for grazing by livestock. The hatched area of 80 hectares (200 acres) shown is the zone intended to benefit from the levee embankments protecting against inundation, from both high tides and floods driven by catchment inflows. The physical footprint of levee bank works that influenced this area is only 1.47 hectares and with a virtually free convict labour source, the task obviously seemed like a worthwhile gamble despite its enormity.

With the benefit of hindsight almost two centuries later, it is doubtful whether the scale of anticipated gains in production were ever realised (much like the Apsley Marshes which were envisioned to become dairy country after being taken up by William Lyne in 1826). Despite subtle differences in the saltmarsh vegetation still visible either side of the levee banks today at Long Point, the wholesale conversion of the land for a major improvement in agricultural production inside the levee bank system does not appear to have ever eventuated.

However, because micro-topography (small changes in elevation) really matters in the way tidal flows and floods interact with the land and behave as flows pass through and inundate saltmarsh communities, and despite the levee banks now being breached in a number of locations, the works are continuing to impact on the eco-hydrology of Long Point. In addition to the physical footprint of disturbed ground preventing natural saltmarsh establishment and zonation where the embankments themselves are situated, the wider ongoing hydrological impact on inundation patterns and flows is something that we are keen to reverse – noting that this is consistent with the fact that the land is now permanently reserved and managed for conservation purposes by the Tasmanian Land Conservancy. Crucially, it will also allow for seamless transitions and upslope migration of saltmarsh communities in readiness for predicted future sea-level rise.

Implementing the plan to restore the hydrology of saltmarsh communities at Long Point

In terms of what we have been doing to address this ongoing impact, NGT recently developed and finalised a hydrological restoration plan for Long Point in consultation with the Tasmanian Land Conservancy, the Department of Natural Resources and Environment and NRM South, which will return the land to its natural state.

Given the wet conditions on-site this year, after another La Niña summer season, we were able to commence some early works to test our restoration methods for the levee embankments, and will return to complete the remainder of remediation works when the site is (hopefully for our purposes) experiencing drier conditions in early 2023.

The simple design philosophy for the levee bank remedial works is summed up by the following illustrated cross-section.

By Mark Bachmann from: Sheldon, R., Bachmann, M., Taylor, B. and Farrington, L. (2022) Improving the Ecological Character of Moulting Lagoon and Apsley Marshes: Long Point and The Grange Hydrological Restoration Plan. A report to NRM South. Nature Glenelg Trust, Hobart, Tasmania.

Overview of autumn 2022 works

Now that we’ve explored the logic of what we planned to do, let’s have a look at the process in action…

The image above shows how the design philosophy is being implemented, where present day disturbance as part of the remediation process is limited to the narrow original disturbance footprint. Note in this image how the levee bank and void still in place south of the excavator, as well as interrupting lateral flows, is not growing saltmarsh vegetation. In fact, if you look closely, you will see how the higher ground on the bank becomes a micro-habitat for weed incursion, with the yellow flowers of a gorse bush clearly visible here growing on top of the bank – but fear not, it is about to have its dry and elevated artificial habitat removed!

In terms of what the remediated ground looks like up close, please see the image below.

There are a few subtle things worth drawing your attention to in this photo. For example, note:

- how the excavator operator has carefully matched the elevation of the remediated ground into natural surface either side of the disturbance footprint.

- how the void has been filled so that the material sits slightly above natural surface. This is to accommodate the expected settling of the now saturated and aerated spoil material that was placed back in the inundated void.

- the difference in vegetation composition either side of the former embankment. This illustrates the impact of almost two centuries of the interruption of high tides and floods, preventing the equalisation of flows through the saltmarsh habitat behind the levee bank. We now expect to see some gradual transitions in the vegetation communities to the left in the image above, as the hydrological regime adjusts in response to the removal of the levee bank.

Now let’s head to the sky to see how the first 360 metres of levee bank remediation work looks from above… Please click through the pages of this pdf to see the story of change since 1948.

Long-Point-works-2022Finally, to wrap things up, here is an oblique image of the completed first phase of works…

Please stay tuned for future newsletters as we will continue to keep you informed about the fascinating project at Moulting Lagoon, including further updates on restoration works in early 2023.

The restoration works being implemented by Nature Glenelg Trust at Long Point have been made possible thanks to the support of the Tasmanian Land Conservancy, as a result of the NRM South project at Moulting Lagoon, with funding provided via the Australian Government’s National Landcare Program.