Managing the interface between agriculture and conservation at Lake Hawdon South

On the 5th of January I visited Lake Hawdon South, 15 km inland from Robe, with members of the South Eastern Water Conservation and Drainage Board (SEWCDB). The purpose was to explore some of the management issues where the artificial Bray Drain enters the wetland. Present were SEWCDB members Miles Hannemann, James Holyman, Jane Featherstonhaugh and Michael Bleby, as well as Ross Anderson (National Parks and Wildlife Service) and local farmer David Hurst.

Lake Hawdon South is a conservation park and one of the most ecologically significant wetlands in the Limestone Coast region of South Australia. It supports internationally significant numbers of the migratory shorebird species sharp-tailed sandpiper (16,430 counted in January 2019), a number of rare and threatened flora and fauna species and a very rare formation of thrombolites (mounds made by cyanobacteria colonies). The conservation park is very large (3,185 ha) with intact, healthy native vegetation. In winter and spring the Bray Drain discharges surface water into the wetland from a cleared, agricultural catchment. Groundwater also plays a role in maintaining inundation of Lake Hawdon South from winter through to mid-summer most years.

Where the Bray Drain enters Lake Hawdon South the drain extends approximately 450 metres into the conservation park. Management of this terminal end of the Bray Drain can also have an impact on agricultural land upstream. Wetland vegetation, specifically a sedgeland of sharp-leaf club-rush (Schoenoplectus pungens), grows in the bed of the drain in this area.

What’s the management challenge?

From the perspective of wetland conservation, vegetation and sedimentation within the terminal end of the Bray Drain is not a problem – in fact, it provides some benefits. The dense sharp-leaf club-rush sedgeland within the drain captures some of the sediment and nutrients in inflows, improving the quality of water entering the wetland, and the sedgeland also provides a small area of habitat in its own right. However, clearly this terminal end of the Bray Drain within the conservation park requires some degree of compromised yet sensitive management to balance the competing objectives of upstream water level management and downstream conservation.

Excavation of the drain has left a spoil mound in the wetland

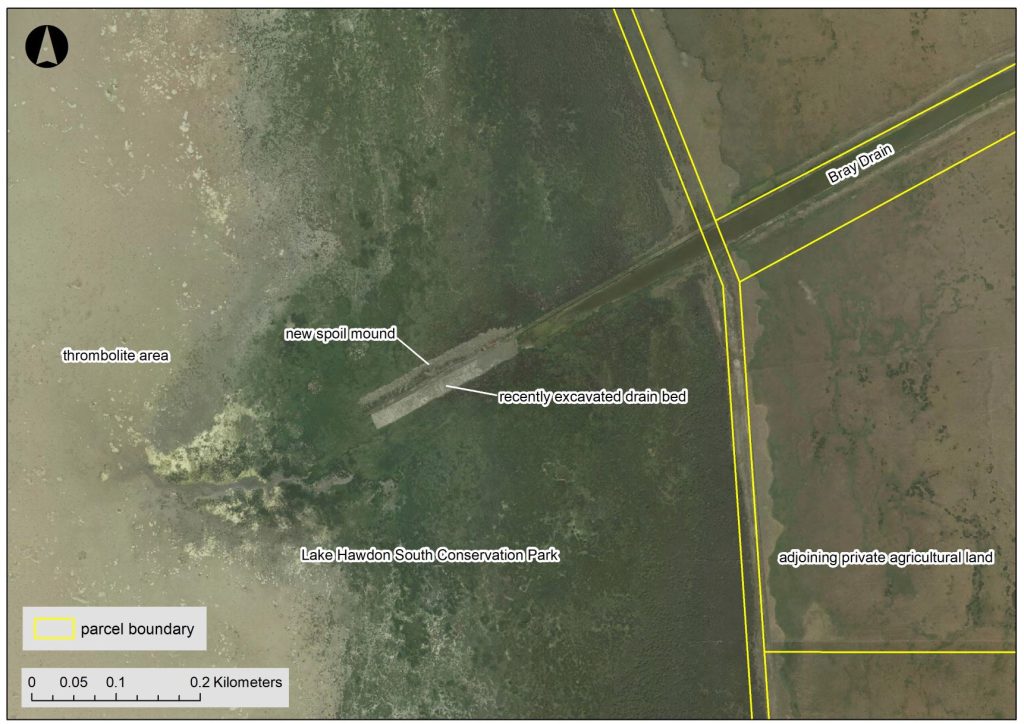

In 2019 contractors engaged by the SEWCDB used an excavator to clear vegetation and accumulated sediment from the terminal end of the Bray Drain within Lake Hawdon South Conservation Park (see image above). Rather than remove the excavated material, it was dumped adjacent to the drain. This created a new spoil mound within the conservation park, extending approximately 200 metres further into the wetland than the pre-existing spoil mound created decades previously.

The problem with this new spoil mound is that it stands approximately 1.5 metres higher than the natural wetland bed in this location. Water levels in Lake Hawdon South never get this high, so the spoil mound remains permanently above the water surface and has become densely covered in a variety of agricultural weeds (see image below). This is both unsightly and a source of weed seeds impacting the surrounding wetland vegetation. Any physical obstruction in a wetland also has a hydraulic effect, with the spoil mound potentially holding water up that would otherwise spread out upon entering the wetland.

Given the ecological significance of Lake Hawdon South this visit provided an opportunity to come together to discuss alternative ways to manage the issues associated with water movement and drain management.

Finding a balanced solution

One method, which is an alternative to physical cleaning using an excavator, is regular slashing of the sedgeland vegetation within the drain. A less preferable approach may be regular spraying of the vegetation to keep the drain clear, noting the sensitive nature of this aquatic environment and the need to carefully manage risks associated with herbicide use in wetlands. While these approaches would require regular (likely annual) effort and expenditure, the total cost over the long-term may be less than the current process of occasional, but expensive, machine excavation. Precedents for this approach already exist in the region. For example, dense reeds between Hacks Lagoon and Bool Lagoon are regularly slashed to clear a flow path, manage upstream water levels and protect agricultural land from flooding.

The downside of regular slashing, for conservation, would be less effective natural filtering of inflows from the Bray Drain. However, this is arguably a compromise worth making if the alternative is the persistence and potential extension of a spoil mound within a significant wetland area. Clearly, a long-term management solution acceptable to all parties (adjoining landholders, the SEWCDB and the NPWS) is required. It should be noted that discussions and planning regarding the removal of the recently created spoil mound have been occurring with the SEWCDB so that the spoil can be carefully removed at the right time.

The importance of the South Eastern Water Conservation and Drainage Board (SEWCDB) in biodiversity conservation

This issue highlights the important role played by the SEWCDB in the management of wetland reserves in the region. Many of the most ecologically important wetlands in the Limestone Coast are connected to the drainage network. Examples include Bool Lagoon, Lake Frome, Lake George, the Mandina Marshes and the Tilley Swamp watercourse. The SEWCDB’s role in biodiversity conservation includes:

- sensitive management of locations, like the terminal end of the Bray Drain, where drains enter protected wetlands;

- protection of important populations that occur within drains, e.g. threatened fish and frogs;

- the operation and maintenance of regulators that control water levels in wetlands and/or divert water into wetlands when opportunities arise;

- the operation of weirs within drains, designed to pass high flows without causing flooding but retain groundwater when flows subside, for both agricultural and ecological benefits.

These tasks require specialist expertise, time and money. An adequately resourced South Eastern Water Conservation and Drainage Board is not just a necessity for agriculture – it is essential to the effective conservation of biodiversity in the Limestone Coast region.