A deeper dive into the history of the Spotted-tailed Quoll

Over the past couple of months of the the NGT newsletter, the Spotted-tailed Quoll has been in the spotlight.

Firstly in October, we took a closer look at the recent quoll capture near Beachport, and then last month, we followed that up with some more interesting accounts from both Victoria and SA, as shared by some of our subscribers.

Since the last installment, Dr David Peacock, who is a Senior Researcher with the University of Adelaide, reached out to point me in the direction of some very interesting papers that reference, among other things, the history of the Spotted-tailed Quoll on the largest of south-eastern Australia’s offshore islands.

Of course, as we talked about back in part 6 of our forgotten fauna series, Tasmania and the mainland have a recent shared evolutionary and ecological history, noting that Tasmania was only isolated from the mainland as the sea level rose after the last ice age. In the process, continental south-eastern Australia’s ancient great coastal plain was flooded and a handful of the higher points were stranded as offshore islands. The largest of these, Kangaroo Island off the present-day South Australian coast, as well as King and Flinders Island in Bass Straight, are the focus of one of the papers. The map below nicely shows how these areas became stranded as the sea level rose.

Map from: Peacock, D.E., Fancourt, B.A., McDowell, M.C. et al. Survival histories of marsupial carnivores on Australian continental shelf islands highlight climate change and Europeans as likely extirpation factors: implications for island predator restoration. Biodivers Conserv 27, 2477–2494 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-018-1546-6

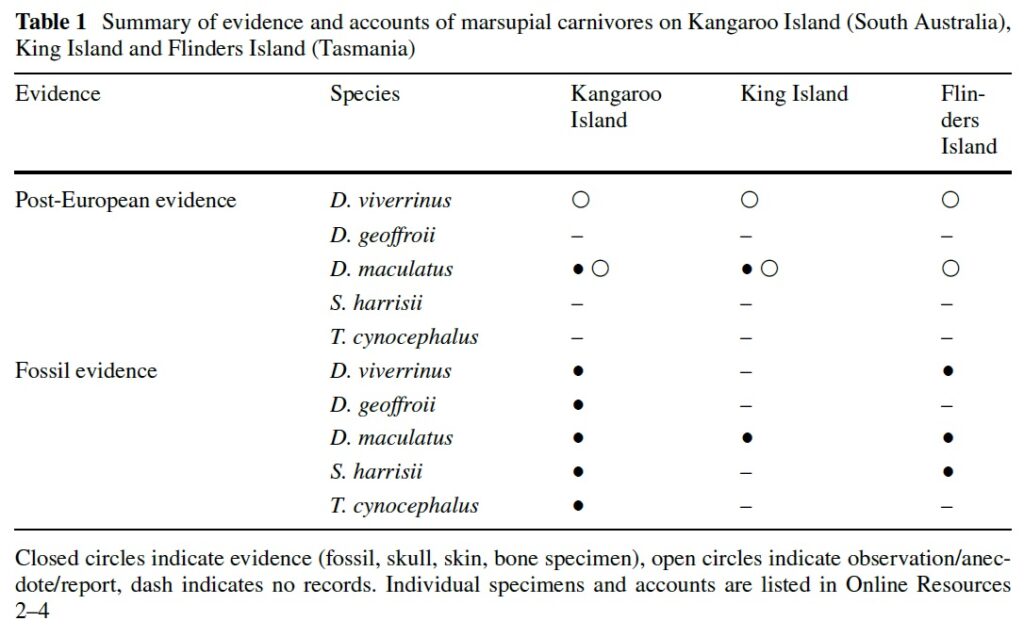

Interestingly, it appears that potentially both the Eastern Quoll (Dasyurus viverrinus) and Spotted-tailed Quoll (D. maculatus) persisted on all three of these islands until European arrival, and for different lengths of time after first contact. On Kangaroo Island and King Island in particular, records of early European observations of the Spotted-tailed Quoll are also supported by hard evidence of an appropriate age, as shown in the table below, reproduced here from the 2018 paper by David Peacock and his co-authors.

Unfortunately, island fauna that have lost their instinctive fear response of humans, after many thousands of years of mainland separation and the absence of people, are especially susceptible when people suddenly reappear. This means that impacts across all three islands, on a wide range of fauna (including some very interesting outliers or unique sub-species), was swift and devastating. For example, did you know that in the early 1800s, Kangaroo Island not only once had quolls, but also dwarf emus, Feather-tailed Gliders, Western Barred Bandicoots and Broad-faced Potoroos as part of its regular suite of wildlife?

The demise of these and other species appears to have been preserved, at least in part and inadvertently, in an early-1800s camp on Kangaroo Island where the skeletal remains of a vast number of small mammals (and other animals) accumulated after trapping and skinning. The camp was likely established by sealers who turned their hand to wallaby (and other small mammal) trapping for their skins. The whole intensive enterprise, which resulted in tens of thousands of animals being trapped and killed, took place before the colony of South Australia even existed (i.e. prior to 1836) and was supported by skillful Palawa (Tasmanian Aboriginal) women who had been forcibly taken to Kangaroo Island from their homeland by the sealers.

A very interesting paper written by Keryn Walshe in 2014 describes this research and outlines the species that were trapped and skinned on Kangaroo Island in this early period of dramatic European impact on the island’s ecology. Called “Archaeological Evidence for a Sealer’s and Wallaby Hunter’s Skinning Site on Kangaroo Island, South Australia”, this paper is also shared below. It is well worth a read.

The final thing I thought would be also worth sharing, is the description of the Spotted-tailed Quoll written by Frederick Wood-Jones in the 1920s for his publication on “The Mammals of South Australia”, given that this has been long out of print.

As you will see at the very end of this excerpt (in the pdf viewer below), he states of the Spotted-tailed Quoll that it was “probably never abundant in South Australia, the stronghold of the species was in the south-eastern portion of the State. It is possible that some few still exist in the less closely settled areas of the South-East.”

As we discovered with the capture of the species near Beachport almost 100 years later, his assessment was eventually proven correct!