Mainland Forgotten Fauna Part 10: let’s talk about rewilding agricultural landscapes, plus deciphering an old account from 1844

The topic of our missing mainland fauna is never far from my thoughts, and a few things have happened recently that have really brought it back into focus.

But before I go through those things, let’s recap a couple ideas from recent blogs that we’ll also touch on in this update:

- in Part 9, we talked about that fact that not all of our missing species collapsed immediately after foxes arrived, with some taking many decades to gradually be lost from the landscape, and

- in Part 8, we talked about ‘shifting baselines’ and how we run the risk of being blinkered in our view of the natural world by only relying on what we have experienced in our lifetimes.

One of the things that got me thinking about this topic again, is the absolutely tremendous news – recently announced in the international media and by the ABC – that an exciting concept Andy Sharp (SA DEW, Northern and Yorke Peninsula) and many others in that community have been working hard for several years to get off the ground, is finally coming to fruition. If you picture the Yorke Peninsula as a foot, the first stage involves fencing across the ‘bridge of the foot’, and the second stage fencing across ‘the ankle’ – as shown – and gradually aiming to bring back the vast majority of their missing fauna to this large experimental area… very inspiring stuff!

The thing that is most exciting about this project is that it is not just focussing on remnant native vegetation (like Innes National Park – at the western tip or ‘toe’ of the peninsula), but is also looking to ‘rewild’ the entire southern Yorke Peninsula landscape including farmland. This means that farmers will also benefit from efforts to reduce fox and cat abundance and the ecosystem services potentially provided by our missing species of wildlife, like Woylies (aka Brush-tailed Bettongs). It is going to be interesting to see just how reintroduced species might begin to use a wider range of habitats, including modified open farmland (as discussed in Part 8) – we just have to shake up the fundamentals of how the ecosystem has been operating, from the top-down.

For a more detailed overview, please see this media release: Rewilding Yorke Peninsula – Natural Resources SA Northern and Yorke.

This is a really fantastic project and, if it just happens to work, it will help everyone in our sector re-evaluate the constrained (dare I say… ‘conservative’, ‘risk-averse’) thinking that currently drives most environmental projects, which are often geographically restricted to public or private reserved areas of bushland. This concept – of finding ways to test key conservation ideas that are capable of sitting along-side or indeed bedded within farms in the wider landscape – actually ties in perfectly with NGT’s recently acquired reserve in the Grampians at Long Point. At this site, we’re beginning to think about the ways we might experiment with the species we discussed in Part 9, like Bush-stone Curlews and Eastern Barred Bandicoots – noting that these species were only lost from the southern Grampians, after long and gradual declines, in the past 20-30 years.

Finally, in doing some historic research for another interesting project at the moment (looking at the history of Tilley Swamp in the upper South East of SA), I came across a fascinating early account that is worth sharing. This passage comes from the journal of Deputy Surveyor General, Thomas Burr, from his trip to the South East of South Australia in April 1844 as a member of the exploration party of Governor Grey. This passage is from the day they left the Coorong and headed south, 25th April 1844:

At one p.m., we came to the Granite Rock. This is, perhaps, the most remarkable feature in the country that we had seen to the east of the River Murray. It consists of a large protruding mass of coarse-grained red granite, with numerous embedded masses of fine grained dark grey granite, and to the N.W. a vein of vitrified quartz rock. The mass rises about twenty or twenty-five feet, and to the N.W. consists of a large smooth mass rising like a blister from the plain; whereas, to the S.E. the masses are irregular, and piled one upon another. There are several small patches with soil, upon which kangaroo grass and casuarina (this is referring to drooping she-oaks) grow. On this rock we saw several kangaroo rats, which belong to a new species. To the E.N.E and S.E. there are several other protruding masses of granite, near to the one described, as also to the N.W. jutting into the sea (now called ‘The Granites’, on the coast north of Kingston).

For anyone who has driven on the coastal road from Salt Creek to Kingston SE, you will immediately recognise the location – it is where the main bitumen highway now crosses from the eastern side of the Coorong ephemeral lakes, across to the other side of the flat to continue along the edge of the coastal dune range.

But talk of “kangaroo rats” in this location is so far removed from our experience of that area today (including – despite its size – the entire Coorong National Park, which is devoid of the previous suite of medium-sized ground-dwelling mammals), that is seems hard to even now imagine. This is a perfect example of a dramatic ‘shifting baseline’.

Early descriptions of “kangaroo rats” or more accurately “rat kangaroos” are likely to be referring to one of the members of the Potoroidae family, which includes what we refer to today as Bettongs, Potoroos and Rat-kangaroos, or possibly a species of Hare-wallaby.

It is interesting to note that Burr considered this to be a new species, hence I think a process of elimination can narrow down which species he possibly saw that day.

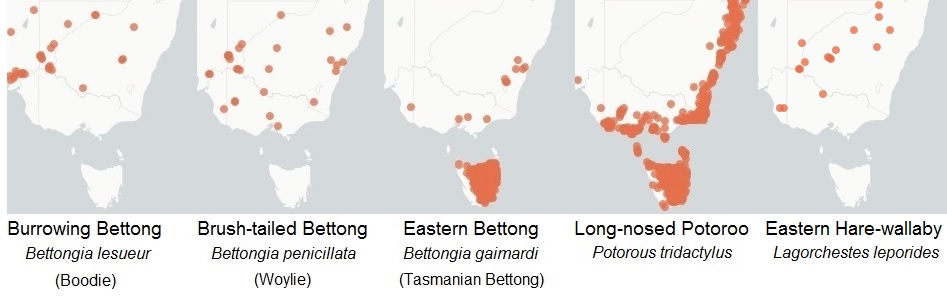

Based on what we now know, it is pretty safe to exclude Rat-kangaroos (of the Genus Aepyprymnus and Caloprymnus) of central and northern Australia, so that leaves three potential species of Bettong (Burrowing, Brush-tailed and Eastern), the Long-nosed Potoroo, and the Eastern Hare-wallaby. The relative distributions of these species, based on the scant (and hence potentially misleading) records compiled by the Atlas of Living Australia are below.

By combining these maps with the information contained within Wood Jones’ seminal work on SA Mammals (1923-25), we can probably eliminate the species that were more commonly encountered along the Murray plains and in closer proximity to Adelaide, because Burr specifically stated that he thought he had seen a ‘new species’. This statement implied that he has some familiarity with the subject and felt that this species was different from what he had encountered previously. This general conclusion is supported by the fact that on his return journey from the lower South East via the same route (on the 13th of May 1844) he stated that he specifically sought out the granite rock “with a view to get one of the kangaroo rats which we had seen there in our outward journey, but the gun would not go off, in consequence of the rain which had fallen since we started having damped the caps“.

My feeling is that this eliminates the Burrowing and Brush-tailed Bettong, and the Eastern Hare-wallaby, which all had typically more arid (and northerly) distributions, and were thus the species potentially more familiar to Burr – also remembering that in the 1800s, each of these species were considered common, but of course that did change dramatically – with them all suffering a precipitous decline to extinction as soon as the fox arrived (from the 1890s). Interestingly, this trajectory of population collapse mirrors the demise of the Eastern Quoll (or Native Cat), that we discussed in Part 9.

Wood Jones illustrated this in the 1920s by stating that:

- the Burrowing Bettong “is as far as I can ascertain, the only species still living in South Australia… In certain districts it is by no means rare, but its decrease in numbers has been so rapid during the past 20 years that probably the remnant still existing will not be regarded as a very long lived one.”

- the Brush-tailed Bettong “only a few years ago, was extremely common over the greater part of South Australia. Twenty years ago, the dealers in Adelaide did a great trade in selling them by the dozen at about ninepence a head for coursing on Sunday afternoons”.

- the Eastern Hare-wallaby (quoting Gould in 1888) was “tolerably abundant in all the plains of South Australia, particularly those situated between the belts of the Murray and the Mountain Ranges” (presumably the eastern flanks of the Mt Lofty Ranges). However, Wood Jones went on to say that only 35 years later, by the 1920s, he had “been unable to obtain any evidence of its present existence in the State, and in all probability it is completely exterminated”.

Based on our current knowledge of Long-nosed Potoroo distribution and habitat use, including in Tasmania where the apex-predator ecological balance has not been as disrupted as on the mainland, it seems less likely that this species, now typically associated with dense, closed habitats, would have been seen in the afternoon on a rocky granite outcrop in a habitat more aptly described as dry grassy woodland.

That leaves the most likely candidate as the Eastern Bettong, a species rarely encountered in South Australia but which (prior to its mainland extinction) was considered to be a coastal species, more associated with open, grassy habitats, and that nests by building shelters (rather than burrowing). This sighting would potentially have also formed the western edge of the species mainland range – as it was more typically associated with the Victorian and NSW coasts – and was therefore more likely to be something Burr hadn’t encountered elsewhere in South Australia.

What do you think, could this be our candidate?

Now of course all of this is pure conjecture, and we’ll have no way of ever knowing for sure, but it is definitely an interesting and challenging exercise to try to decipher these old accounts from the limited information now at our disposal.

The point of all this is to say, let’s not lose hope of bringing these critters back to our corner of the mainland – and let’s keep talking about them. After all, they form a legitimate part of our natural history, and while we have their cousins still hanging on across in Tassie, they might be gone for now, but they should definitely not be forgotten.

The project getting underway on Yorke Peninsula is a great step in the right direction for injecting a bit of much needed inspiration into ‘re-imagining’ what conservation projects can look like in our temperate agricultural regions. There is still so much we can do (or test / trial), if we just think outside the square…