It’s a sign: Interpreting the flood response of River Red Gums

I was lucky enough to spend a couple of days at Lake Hattah over the June long weekend and it got me thinking about our view of the landscape and what it tells us. As ecologists, reading the landscape and interpreting what’s going on is part of the job. At the Ramsar listed Lake Hattah, the River Red Gums (Eucalyptus camaldulensis) tell a pretty interesting tale. South of the Murray floodplain we don’t have very many Red Gum fringed swamps protected for conservation, that are also in decent hydrological condition, so this was a rare treat.

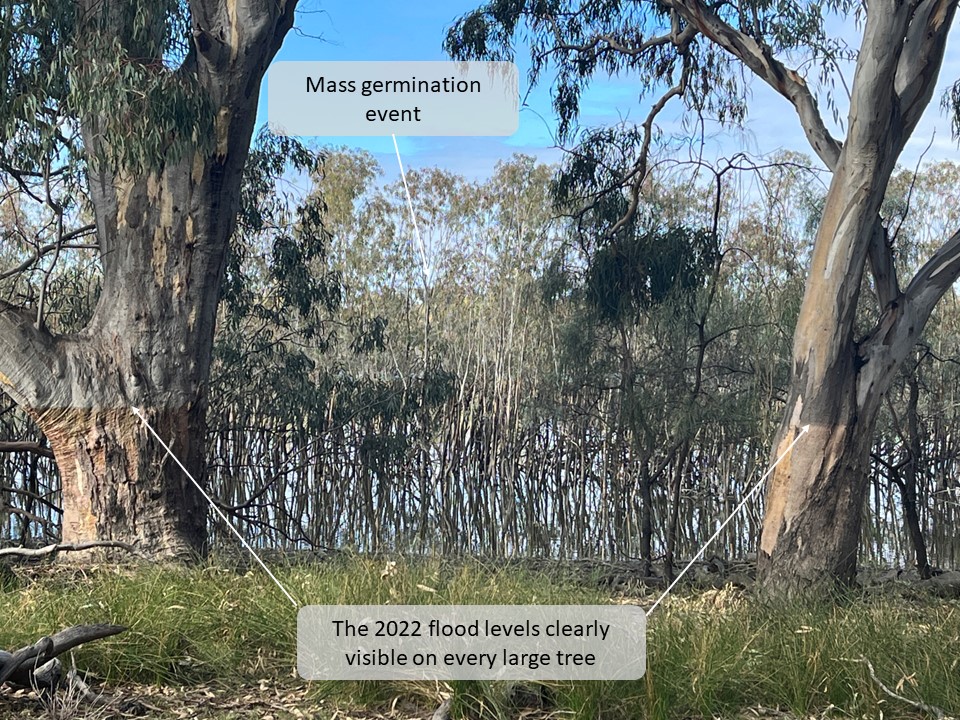

They say a picture is worth a thousand words and this picture has some pretty clear messages.

This photo tells us quite clearly where the 2022 flood levels peaked, but also that there was another flood event perhaps 6-10 years ago, that produced a flush of germinants around the wetland, perhaps the 2016 floods, or a slightly earlier flood event. The two big trees, which are part of a ring around the Western edge of the wetland would themselves have established decades ago in a similar event, and there are many even larger trees at the site which must be truly ancient. Age classing Red Gums is a challenge but they grow very quickly for the first few years and relatively slowly after that, so these larger trees could even be centuries old.

River Red Gums are the most widespread Eucalypt species in Australia, found in all mainland states, and there aren’t too many people who wouldn’t recognise them. Their affinity for lining waterways and wrapping around wetlands, plus their ability to persist as sentinels across wet flats for centuries makes them especially recognisable and easy for us to identify with and value. However, they didn’t persist across the landscape and thrive in some of the driest and wettest parts of the country without some pretty impressive adaptations.

River Red Gums germinate after floods and the mass germination events can be a very helpful indicator of how high (i.e. depth) and how far (i.e. extent) the water got before receding and depositing seed. As the very small light seed floats, it is guided by either flow or wind and after a suitable period of soaking, is deposited and germinates. This need for prolonged soaking ensures that they only germinate when there is enough water around to give them a good head start. Pretty smart for a plant that grows in some very arid places!

To survive through to adulthood the seedlings require regular access to water for the first few years. As they germinate en masse, it’s a fight for survival against their siblings and only the strongest will eventually become the gnarly, hollow-filled adults that we so admire.

In south-western Victoria we also see similar behaviour to this around wetlands, where stock grazing of the young plants is excluded. The photo below shows an old Red Gum at Walker Swamp with another cohort, all of similar ages (judging by the trunk diameters) around it.

However, south of the Grampians and across into South Australia, we also have the iconic Red Gum flats where the tenacious old trees are often the only remnants of the open grassy woodland/shallow wetland matrix that existed on a vast scale prior to European arrival. Regardless of where Red Gums occur they have the same dependence on water to be healthy and to reproduce. Wetting of the seed for a prolonged period is always necessary for germination.

Other impressive adaptations allow the trees to survive in standing water or waterlogged soil for periods of months, with no ill effects. They do this by having deep extensive roots, some of which contain a spongy, air-filled tissue called aerenchyma that allows for the accumulation and transport of much-needed oxygen in waterlogged soils. Alternatively, they can survive in drought by dropping many of their leaves to reduce water demand, one reason they often look bedraggled over a hot summer.

River Red Gums continue to survive in our much altered landscape, providing biodiversity values that are really impossible to measure. But if you are looking at a Red Gum dominated landscape and all the trees are the same size (and therefore age) it is telling you that something is out of balance. Either there is not enough water, for long enough, to support germination. Or alternatively all the young plants are getting knocked off by grazing, competition from weeds or disturbance of their roots. Trees that are stressed are susceptible to fungal and insect damage.

If we want to see our Red Gums survive, not as lone survivors, but as part of the healthy ecosystems they should be a part of, they need just a little protection, restoration and support to thrive. They are after all one of our hardiest and most adaptable species.

At NGT we take a great interest in the Red Gums on our reserves and are watching them closely, and monitoring how they are responding to the recent wet conditions, the removal of competing blue gums and the impacts of altered grazing pressure. Reinstating regular, and cooler fire in the landscape is a key step in improving the condition of grassy woodlands and wetlands that we will continue to explore further. We’re also keen to understand impacts of insects on plant health and survival (including the incidence and impacts of Psyllid or lerp attacks on tree health). We monitor the health of the Red gums on our properties at regular intervals, and you can read more about our intrepid volunteers and their efforts to monitor 100 trees at Walker Swamp here. We also have some tree monitoring days coming up, see details here.

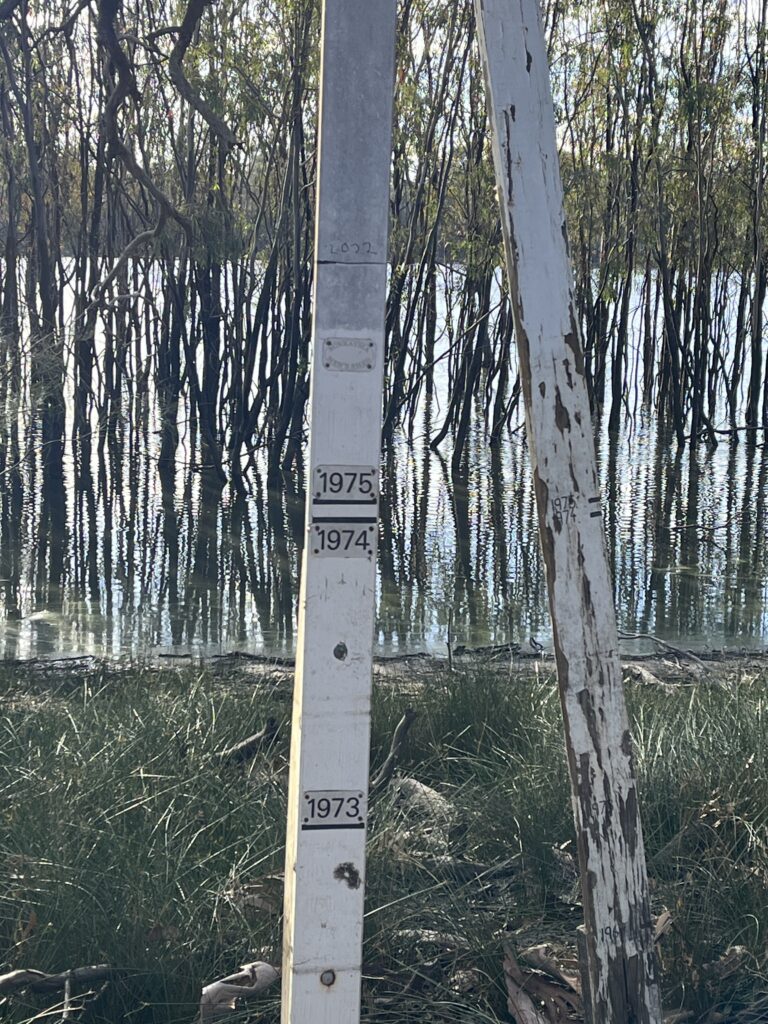

And a final sign… which is much easier to read!

The flood marker from Lake Hattah, showing the 2022 flood relative to the other major floods, the legendary 1956 floods were at the top of the marker (not shown) by a substantial margin, but must have really been something to see!