What can the early maps tell us about the eco-hydrology of Burdens Marsh?

In last month’s story, we started to put together a timeline of events that helps to explain the early drainage history of Burdens Marsh, a significant area of saltmarsh habitat within the Tasmanian Land Conservancy’s Sloping Main Reserve. As our investigation continues, we’ve been able to dig a little deeper, so this time around we’ll take a closer look at the early maps to see what else we can learn about the timing of drainage works that were in place prior to the first aerial imagery being flown in the 1940s.

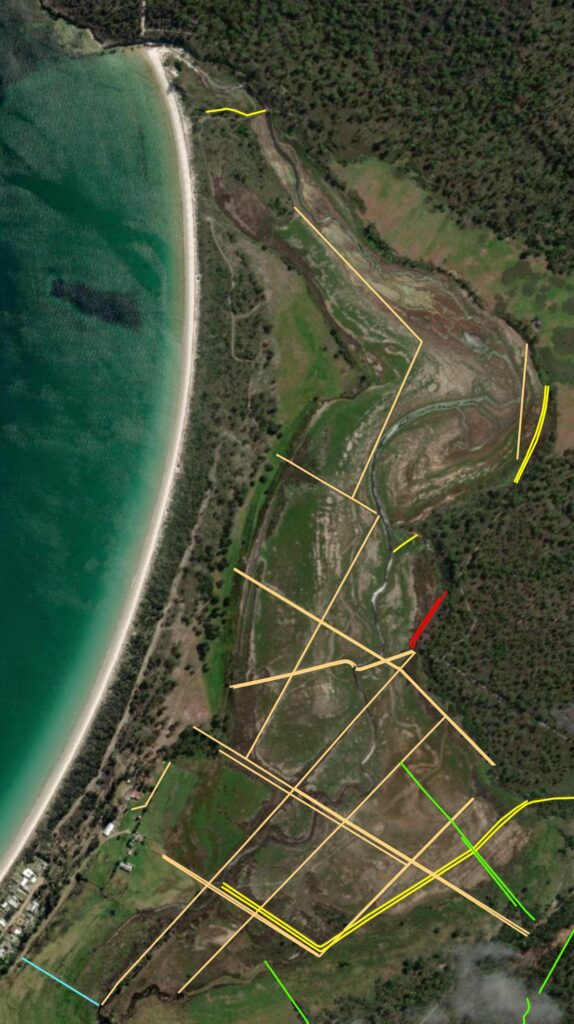

The oldest drains, thought by locals to have been constructed in convict times, are marked in a light brown colour in the map below, while drains constructed since the 1960s are marked in other colours. So, let’s fossick around, and see what we can uncover…

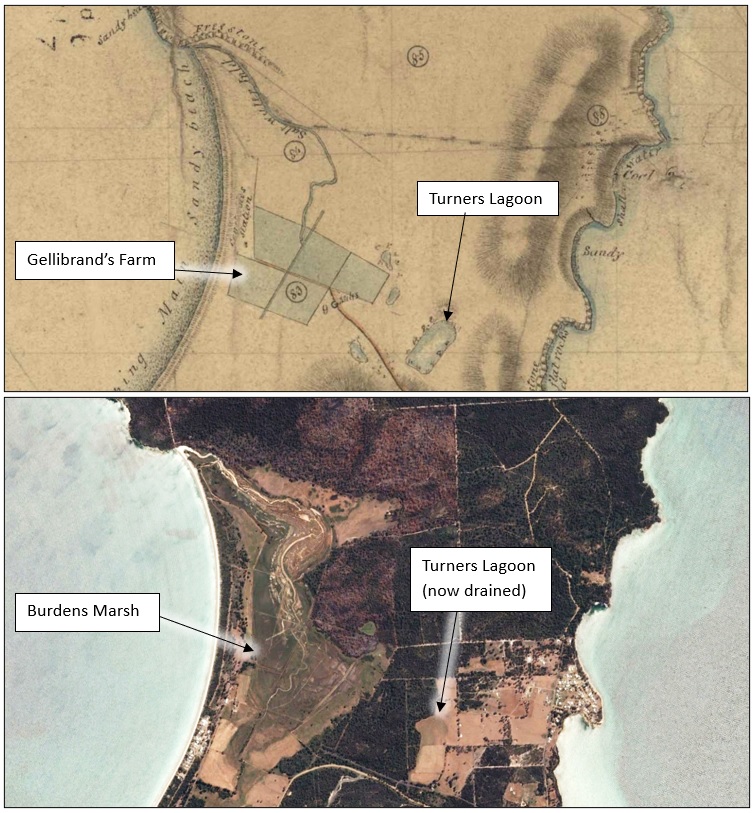

One of the earliest maps that shows any level of detail at Sloping Main was based on a survey completed by James Hughes in 1833, just after coal had been discovered nearby and as the new Penal Settlement at Port Arthur and its various outstations across the Tasman Peninsula were getting up and running. Despite prior orders to leave, the Tasman Peninsula’s one resident settler, Joseph Gellibrand, was still occupying his new farm at Sloping Main, and we are fortunate that the dimensions of his farm and its early drainage network (likely dug in the late 1820s) were represented accurately on this map!

The reason that we can confidently say that this map is relatively accurate, is because Gellibrand’s farm layout can be seen – literally still etched (via the Digital Terrain Model based on LiDAR) into the landscape today, and we have a perfect match!

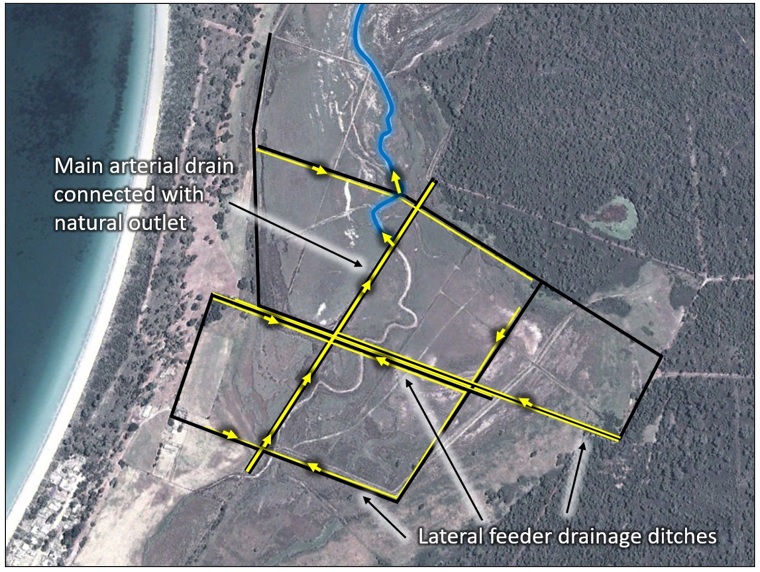

Below is a summary of what we have so far inferred that the original drainage and paddock layout may have looked like.

Confirmation of this site, as the location of Gellibrand’s original land selection on the Tasman Peninsula, is supported by additional evidence from the archives in 1833. Although he had been given earlier instructions to leave, at that time Gellibrand was still occupying land at Sloping Main with cattle loose on the Peninsula, frustrating the new commandant of Port Arthur, Captain Booth, who arrived at Port Arthur in March 1833 and wrote to his superior officer about the lingering situation in October of that year.

Governor Arthur replied to Captain Booth’s complaint by stating that he had given clear instructions:

“that Mr Gellibrand’s establishment on Sloping Main should be immediately removed. Intimate to that gentleman that after the repeated notices that he had received, any further delay in removing is now wholly out of the question, and it is at the present moment a matter of extreme necessity that he should forthwith withdraw his establishment as the Government are just about to form a working party on the spot.”

It seems that a short time later Gellibrand did eventually vacate the site and, with the departure of its last free settler c.1834, so began a long period where the Tasman Peninsula functioned as an open air prison – fiercely guarded at Eaglehawk Neck – until its eventual closure in 1877.

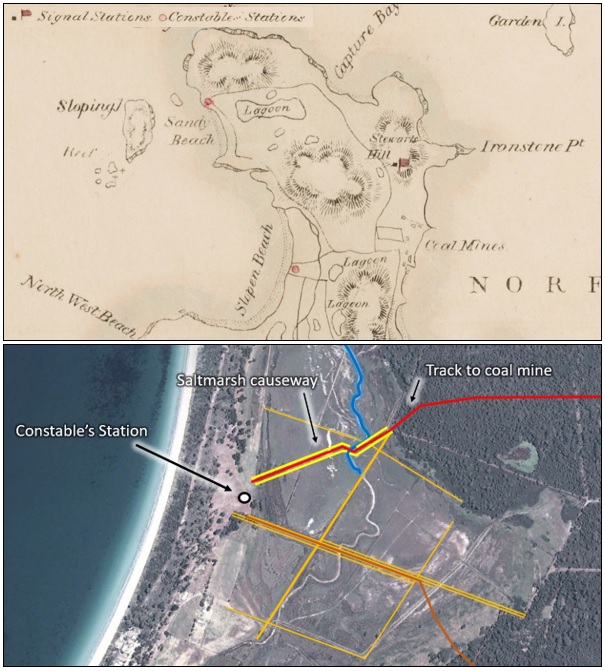

After digging through the archives, it has become apparent that – although at least part of the saltmarsh at Sloping Main was grazed in the convict era from the early 1840s – there is no evidence that any further major coordinated drainage works took place. The only minor exception to this was the construction of a new causeway across the marsh after Gellibrand departed, sometime in the 1830s, to provide a more direct track from Sloping Main to the newly established coal mine nearby.

We know this because the new track is shown in a map from 1841 and others of the same era, plus the evidence for this diagonal causeway is still visible on the ground today. Not surprisingly, this track crossing led directly to the Constable Station at Sloping Main, as shown below.

BELOW: Works that date to the mid-1830s through the saltmarsh, providing more direct access to the coal mines. The red line indicates the location of the new track and the yellow lines are the ditches that were dug either side to gain the material required to create the causeway. Earlier works are marked in orange (drains) and brown (roads).

With the departure of the last convicts in 1877, the government began holding auctions of Crown Land to open up the Tasman Peninsula to free settlers. The bulk of the saltmarsh at Sloping Main was selected by Jacob Burden in 1878, after whom Burdens Marsh is now named. The map drawn in 1877 of this area includes the first detailed perspective of Burdens Marsh after European colonisation – note that you can use the pdf viewer below to zoom in and read some of the interesting notations…

Fig-7-AF396-1-1121In terms of features drawn on this plan, it provides us with our first detailed glimpse into the physical appearance and condition of the saltmarsh at Sloping Main, at the conclusion of the convict era in 1877.

Key items of note include:

- The original arterial north-south drain dug by Gellibrand prior to 1834 is still present, with a surveyed drainage reserve indicating its location.

- The lack of cultivation in the paddocks set up by Gellibrand is apparent, with the following vegetation notation written across this central part of the saltmarsh area: “Marsh with belts of scrub”.

- The outlet is shown as being open and flowing.

- A longer notation in the bottom corner of the map says:

“Greater portion of Marsh is at time overflown with Salt water, forced over the bar in heavy weather, as high tides, a slight outlay would obviate this, and the land would make an excellent dairy farm, 4 lots of 30 to 40 acres are of good soil suitable for cultivation, there is scarcely any timber on these lots.” - In the centre of Jacob Burden’s allotments there is a signed notation with the date “9/5/91” marked on the plan, which may indicate that the credit terms of the original land purchase were met on that date, almost 13 years after the auction. One month later, on 3rd June 1891, Jacob Burden was issued a Purchase Grant (i.e. title to the land) formalising his freehold ownership of the property.

Was the period after Jacob Burden’s purchase, between 1878 and 1890, the era when additional drainage works were undertaken through the saltmarsh? It is difficult to say for certain, but here are some factors to consider:

- There is so far no hard evidence that any works to enhance the earlier (pre-1834) drainage of Burdens Marsh were completed during the convict era (1834-1877), but this is not conclusive, because most of the drainage detail is lacking on the 1877 survey plan.

- Given the land capability information noted by the surveyor, it is conceivable that Jacob Burden purchased the land encouraged by the prospect (as noted by the surveyor) of improving (or working with) the existing drainage works and making it more productive for livestock grazing.

- Being purchased on credit means that Jacob Burden would have been seeking ways to make the country provide a return. Ultimately it appears that he paid off his loan to the government a little more than a year early.

- Yet, if Jacob Burden was keen to undertake more major drainage works, how would have he managed the cost of this as an indebted sole farmer, without access to convict labour, at a time long-before the advent of mechanical digging equipment?

- We do know that the original drainage network was considered to have been ‘long in place’ by the time that the Price family purchased this area in 1932, and no major works were completed by them between 1932 and the 1940s, when the first aerial photographs of the area were taken.

In summary, the remaining drainage works that were in place after 1834 but prior to the commencement of the photographic record in 1948, as summarised in the map below.

If you are interested to learn more, then please keep an eye on future newsletters.

For the history buffs, an expanded version of this story will be included in our eco-hydrological assessment report for the TLC, which is currently under development. This report will also investigate what we can do to overcome some of these legacy impacts from past land-use, to set this important wetland area on a long-term, self-sustaining trajectory of ecological improvement and recovery.

This project is being delivered by NGT in partnership with the Tasmanian Land Conservancy,

with support from the Purryburry Trust